Category: Metal Detecting

Volunteering at Detectival

It’s taken me a long time to sit down and finally want to write this blog post. That’s because for many who dabble in the wonderful hobby of metal detecting it can be, and very often is an emotional past time. There are a myriad of reasons for the emotional side of searching for the past in the ground, all of which I think are good for the soul. For some it’s the thrill that comes with finding Iron Age or Roman coins and artefacts, or any historical finds for that matter. For others it’s being out in the country air which can be a great tonic for the stresses that life can bring. For a lot of us it’s a combination of both, although detecting can bring it’s own stress in the form of frustration when a day out doesn’t produce in the way that you think it should.

The reason it’s taken so long for me to sit down and write this is simply because I didn’t know how I would approach it. Decetctival 2025 was very conflicting for me because it took place on a permission which I have been detecting on for quite a few years now. I’m out on this permission most of my free weekends and I have come to know the place really well through research and endless hours walking in the fields. So when I found out that Detectival was going to take place here my heart sank. The thought of 1500+ detectorists searching the permission that I have come to know and love filled me with a certain amount of dread.

Coming to terms

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against group digs, they are a brilliant way for people to take part in the hobby who haven’t been able to get their own permissions. I have been on a few smaller group digs myself when I was starting out and they have certainly helped in fueling what is now a life long passion for this hobby. But, and this is where I am going to sound like a NIMBY, it’s a completely different proposition when one of these events takes place on your own permission, especially one the size of Detectival.

I found out about six weeks before the event took place when a lot of the fields still had crops in. There were a lot fields I had been waiting to get into which meant when they became available it only gave me a few weekends to search them before Detectival took place. The fields in question had a mix of Iron Age, Roman and Medieval features all of which have given up good finds in previous years. So I spent those weekends searching as much of those fields as I could, and they didn’t disappoint as you can see in Figs.1-6.

Embrace the inevitable

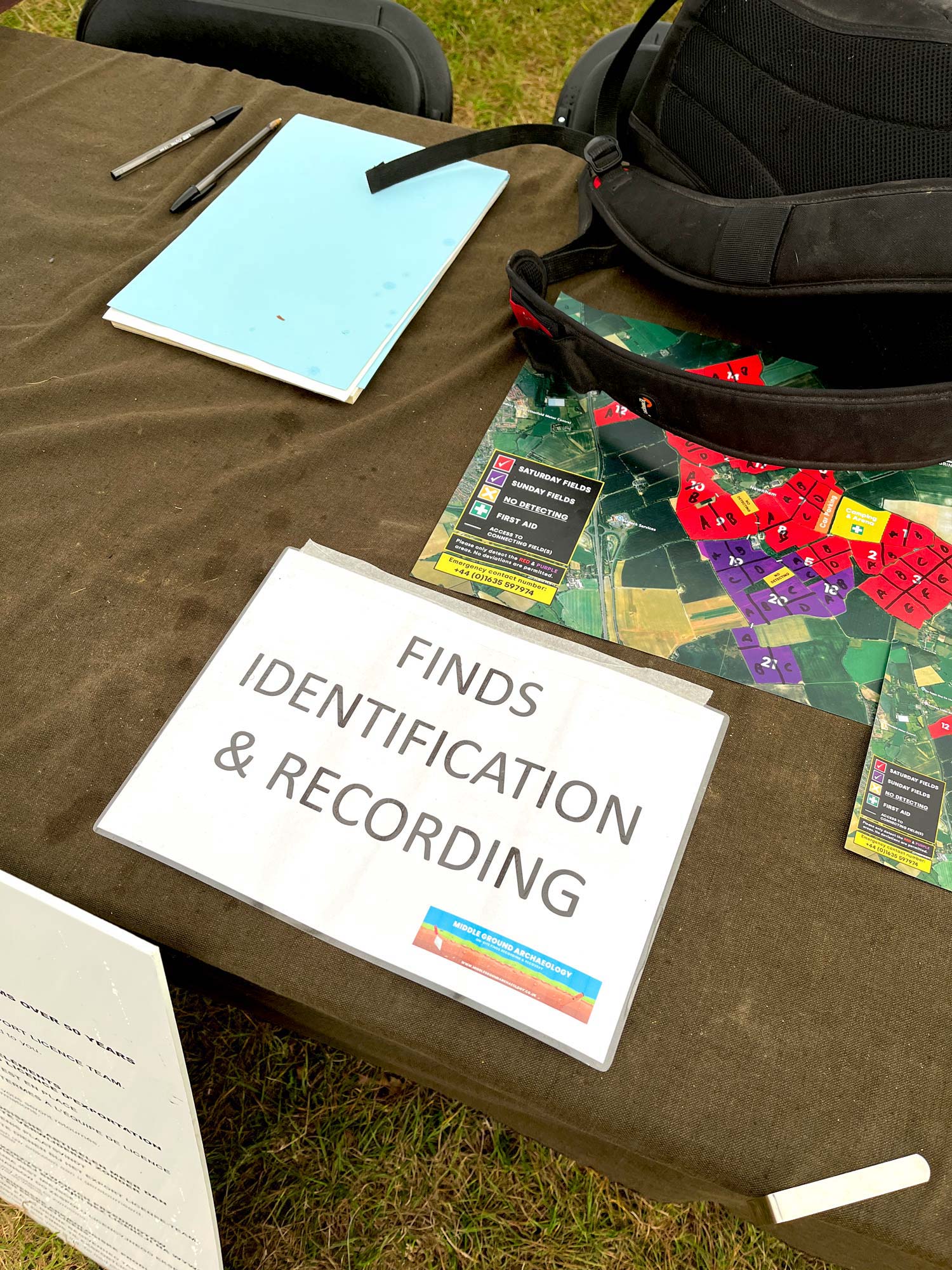

I decided to embrace Detectival taking place on my permission, after all there was nothing I could do about it. But then an unexpected opportunity presented itself which I couldn’t turn down. For the past year I have been a member of the North Hertfordshire Archaeological Society, and they were approached by Anni Byard, the Archaeologist & Small Finds Specialist who heads up the finds team (Middle Ground Archaeology) for Detectival. She was looking for volunteers to help record the finds over the weekend, so of course I Jumped at the chance. I figured it would be great to get a different perspective on our hobby and see what life is really like recording finds.

I was due to help out in the finds tent on the Sunday, so I decided to do a bit of detecting on the Saturday. Taking to one side meeting some brilliant people, I have to admit that I didn’t enjoy the detecting part of it, being surrounded by crowds of detectorists on my permission was not fun. One of the many things I love about detecting is the solitude of being on my own or sometimes with a mate or two, but this… nah, not for me. Unsurprisingly on my short lived session I didn’t really find anything of note, other than one of the musical variety (note that is) which I think was once an earring (Fig.7). Still, it’s always nice to have a bit of silver up.

A day in the life

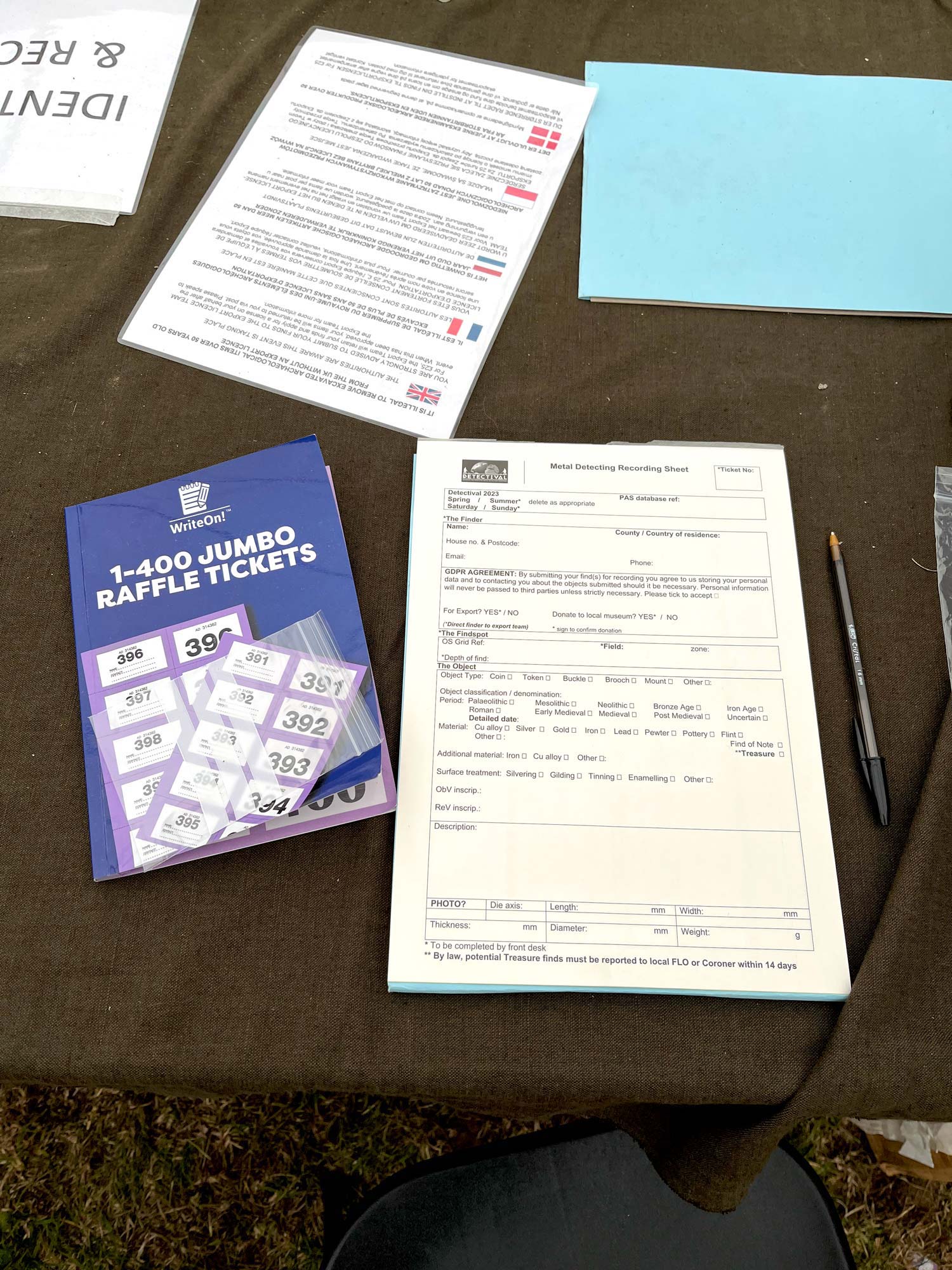

On Sunday I turned up at the finds tent a little before time and settled in with a nice cup of tea whilst introducing myself to a few others who were already there. The finds tent was due to open at 10:00am so at 9:30am Anni Byard introduced herself to us all and talked us through the processes we would be involved with for the day. I was tasked along with 3 or 4 others with recording the finds as they came in using the handwritten forms shown in Figs.8-9. This really did feel like being thrown in at the deep end as the detectorists and their finds came in thick and fast.

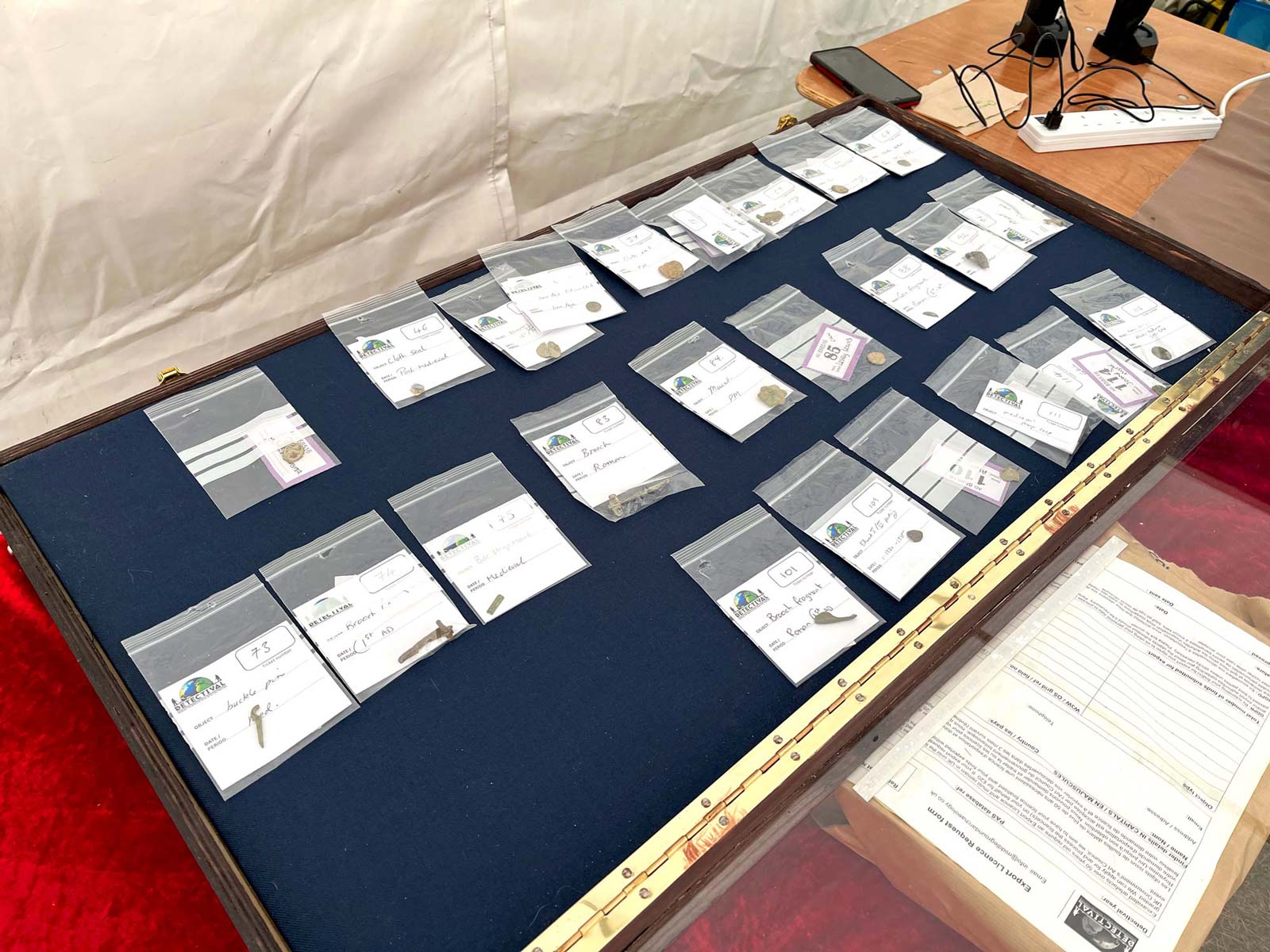

Initially I was going to write an article about the detectorists and their finds thinking that working in the finds tent would give me the time to talk to people, but boy was I wrong. The process of recording finds went as fast as we could write, and being that most detectorists had more than one find to record the pace was pretty slow. Each find had to be recorded individually with the details of the finder and the rough location of the find spot. The finds were then bagged with a numbered ticket, this number was written on the finds form and the other half of the ticket was given to the finder. The finds with their forms were then passed back to the brilliant archaeologists and finds specialists, who then went through the unenviable process of identifying, photographing and writing up their descriptions of the finds to complete the forms. Once this was done the find itself went into the return display (Fig.10) where the finders could present their numbered tickets and retrieve their finds.

Although the process was slow the day itself went pretty quick, probably the result of us being very busy for most of it. I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to work with the Middle Ground Archaeology team and to get a glimpse of what goes on when I leave my finds with my local finds liason officer. It has certainly opened my eyes to the incredible amount of work they have to do, and because our hobby is growing in popularity that work is becoming increasingly harder. Many detectorists (including myself) moan about the fact that we’re having to wait month’s, even years sometimes to collect the finds we hand in to be recorded. Currently I have waited over a year to pick up my latest set of finds, so I get the frustration that many (again including myself) feel about having to wait so long. But experiencing first hand the work that archaeologists, finds specialists and finds liason officers have to do recording finds, I now have a bit more understanding of their timescales and a little less frustration towards it. Talking to some of the archaeologists and finds specialists on the day it seems the problem is lack of staff which in turn is due to lack of funding, an issue which unfortunately isn’t felt by the Portable Antiquties Scheme alone.

The day ended with a group shot of the finds recording team shown in Fig.11 (I’m on the right handside wearing a white t-shirt). This was a great combination of professional archaeologists, finds specialists and volunteers working together for the benefit of those detectorists giving up their time to search for history. I met some brilliant people and saw some amazing finds, although there was a small part of me thinking ‘those finds should have been my discoveries’. But on the other hand this permission is huge and I could spend the rest of my life detecting here and miss most of the things that were found this weekend, well thats the thought I’m comforting myself with.

Life after detectival

So now the behemoth event that is Detectival has left town and I’m back to the wonderful solitude on this permission (Fig.12). The event itself seemed to go pretty well and was extremely well organised. On the Saturday when I was part of the crowd everyone seemed to be having a good time. Wether they were detecting, eating from the food vendors, having a few drinks listening to live music, chatting to the various experts from the leading detecting brands or just enjoying the wonderful North Hertfordshire countryside, the atmosphere was great. What struck me most is that the detecting community is a welcoming, friendly and embracing one. I think it’s because of the passion we all share for this amazing hobby, that passion just ouses out of you when you’re chatting to fellow detectorists which in turn creates that friendly and embracing atmosphere. With the way things are in world events at the moment I think human beings need more of this kind of feeling, maybe detecting is the answer to world peace, lol.

Thankfully for me and the few other detectorists who detect here on a regular basis, some of the fields on this permission weren’t available to Detectival. This is manly due to crops still be in but it’s something we are incredibly grateful for. To stand in some of the fields directly after the event and look at the sea of footprints and refilled holes was quite depressing. Going into any field that was available to Detectival felt like a pointless endeavour as they were all the same, foot prints and refilled holes. So when the crops came out of the remaining fields it was a relief and game on again.

As you can see in Figs.13-17 some fantastic finds have come up for me since Detectival, some of my best from this permission in fact. The sestertius of Trajan is one of the best condition Roman coins I have ever found, with it’s size and weight making it such a lovely object to touch and hold. The silver ‘stag’ unit of Tasciovanus is one of the rarest objects I have ever found, with I believe only a dozen recorded examples. So this permission still has some burried secrets to give up for me to share with you which keeps me and my passion for this hobby very happy. I have no doubt that when the fields many of you experienced at Detectival are ploughed again they will bring up a few more amazing lost artefacts wanting to be found. And you can be absolutely sure, if i find them then I will share there discoveries with you on my Instagram feed. As always the link to my Instagram is just below, go on you know you want to follow the Hertfordshire History Hunter.

WM 09 – Freedom of choice

Last year I had an issue with the Minelab ML 85 headphones which came with my equinox 900. The volume button on the side of the headphones stopped working which made for a lack lustre experience whilst out detecting. They were under warranty so I sent them back explaining the issue to LP Metal Detecting, from who I originally purchased my Equinox 900. LP, as always were brilliant, and a new set of headphones were sent out in a matter of days. But whilst I was waiting for my headphones to arrive I decided to look at what options there were for alternative headphones to use with the Equinox 900, and surprisingly there wasn’t any.

It turns out the only wireless headphones that can be used with my detector are the limited offerings from Minlab, the ML-85 and the ML-105. The ML-85’s that I had were ok and I can’t really fault them as a set of wireless headphones for a metal detector, but they do have some issues. This mainly comes from the fact that they are an ‘over-ear’ design, which does have benefits but also has drawbacks. The two issues for me are that in winter it stops me from wearing my thick knit beanie and in summer my ears sweat like Jabba the Hutt in a rebel sauna!

I thought that this was something that I would just have to live with, until that is I lost my second pair of ML-85 headphones. How did you loose them I hear you ask? It pains me to have to admit it, but I will as it enlightened me to the possibilities that were presented as a result of the loss. Ok, here goes, I left them on the roof of the car as I was packing my gear in the boot! Sad I know but there it is, I drove off and somewhere along the journey the headphones took a leap from the roof of my car. I only noticed a few days later when I went detecting again, obviously I realised what must have happened and went back to the same spot just incase they were there, but to no avail. For that session I used the old wired headphones from my Equinox 600 and I soon realised how much of an inconvenience having your headphones physically tethered to your detector actually is.

Now I was in the market for another set of headphones, so back to the LP Metal Detecting website I went. I was just about to click on the link for a new set of ML-85’s when I noticed this little black box called the Minelab WM 09 Wireless Audio Module. This little gadget is designed to give you the freedom to use whatever wired headphones you want (wirelessly) with my Minelab Equinox 900. Now, I know a lot of people are going to pick up on the fact that it enables me to use wired headphones and not wireless, but for me at least this is a good thing.

I have never really been a fan of wireless headphones for two reasons, the first of which is I’m not keen on the wireless reception being that close to my head. Call me a conspiracy tin hat wearer if you want (I’m not BTW), but if I have a choice to use wired headphones over wireless ones then I will. Secondly I think you get a much better quality headphone for your money with wired versions as you are not paying the extra for the wireless technology. A case in point was when I purchased a pair of Sennheiser Momentum 2.0 headphones, they had the option of being wired or wireless, exactly the same headphones but with a difference of about £100 for the wireless version, wired seemed like a no brainer for me.

So knowing that the WM 09 would give me the freedom to use my own wired headphones made it a very easy purchase. I do think the price at £169 is a little excessive for what it is, but with the 10% discount which you can get from the many detectorists who are affiliated with LP does make it a little more palatable.

There isn’t a huge amount I can say about the device itself as it’s quite simple in both deign and what it delivers. There are two buttons on the front, one to turn it on and the other to connect it wirelessly to the detector. The LED between the two buttons flashes blue when you turn it on and then when you have paired it with your detector it will periodically flash to indicate the connection is secure. The LED on the bottom right will show red when the battery is running low, and when charging it will flash green, then turning to solid green when its fully charged (exactly the same as the Equinox 900 charging sequence) .

It’s a cool looking gadget which wouldn’t look out of place on Batman’s utility belt, should he ever need to go detecting that is. On the back of the WM 09 is a well designed clip which enables me to attach it to my belt or any point of fixation on my batman… er sorry, detecting utility vest. But it’s what this little black box offers in terms of choice which has won me over, and that is I get to wear my favourite IEM’s the Fiio FH3’s which connect easily to the WM 09’s 3.5mm headphone socket.

This immediately solves my two issues with the ML-85 over ear headphones. I can now wear my thick knit beanie in the winter and snugly keep my ears warm without the bulky over ear cups getting in the way, and as I found out on my first detecting session using my new audio system, no more sweaty ears in the hot sun! I honestly think Minelab have done themselves a great service making this device available for their new range of detectors and it’s made me very happy in the process.

As I said earlier the wired IEM’s that I’m using are Fiio’s FH3’s, which for entry level audiophile headphones are bloody brilliant. I have been super impressed with these headphones which I use regularly with my iPod, and I now benefit from that a better quality of sound for my detecting. The physical aspect of using wired headphones is no issue either as I just run the wire under my t-shirt which keeps it from getting in the way of detecting and digging as it’s not directly attached to the detector.

This short review is not finished yet so I will come back to it towards the end of the year when I have got some proper hours under my belt using this new set up. So far the ease of use and the freedom it has given me to wear my own headphones is a big win, but the ultimate conclusion will come with time. Transitioning from summer to winter in the coming months means I can test this device in both the scenarios in which I think it will make my life easier. The more uncertain test from here on then is whether the wireless connection to my detector that WM09 will provide is any good?

The big permission

Back in 2022 I wrote an article for the September edition of Treasure Hunting Magazine titled “Where have all the finds gone?”. At the end of that article I mentioned that my time there had come to an end for that season, but I wouldn’t get to go back out on these fields for another couple of years.

Detecting on this permission began again in January 2024, and now that I had a map outlining all the fields which were part of this permission I was able to do some proper research into the area. This included using Google Earth, the Heritage England Aerial Archaeology Mapping Explorer, the Heritage England Aerial Photo Explorer, and scouring through endless aerial photos on the Cambridge Air Photos website. Having access to all these online tools gave me a brilliant insight into where would be good locations to start the detecting journey here once again. I spent my first afternoon in a field which was next to the one that contained the Roman villa which featured in the 2022 article. Not a lot came up, but on walking back to the car these two little silver gems in Fig.1 appeared. The brooch, with a thistle design, is hallmarked which tells me it was made in Chester in 1913 by Charles Horner, the button, though a bit worse for wear, is roughly dated to the 18th Century (Georgian), a nice end to an otherwise crappy afternoon.

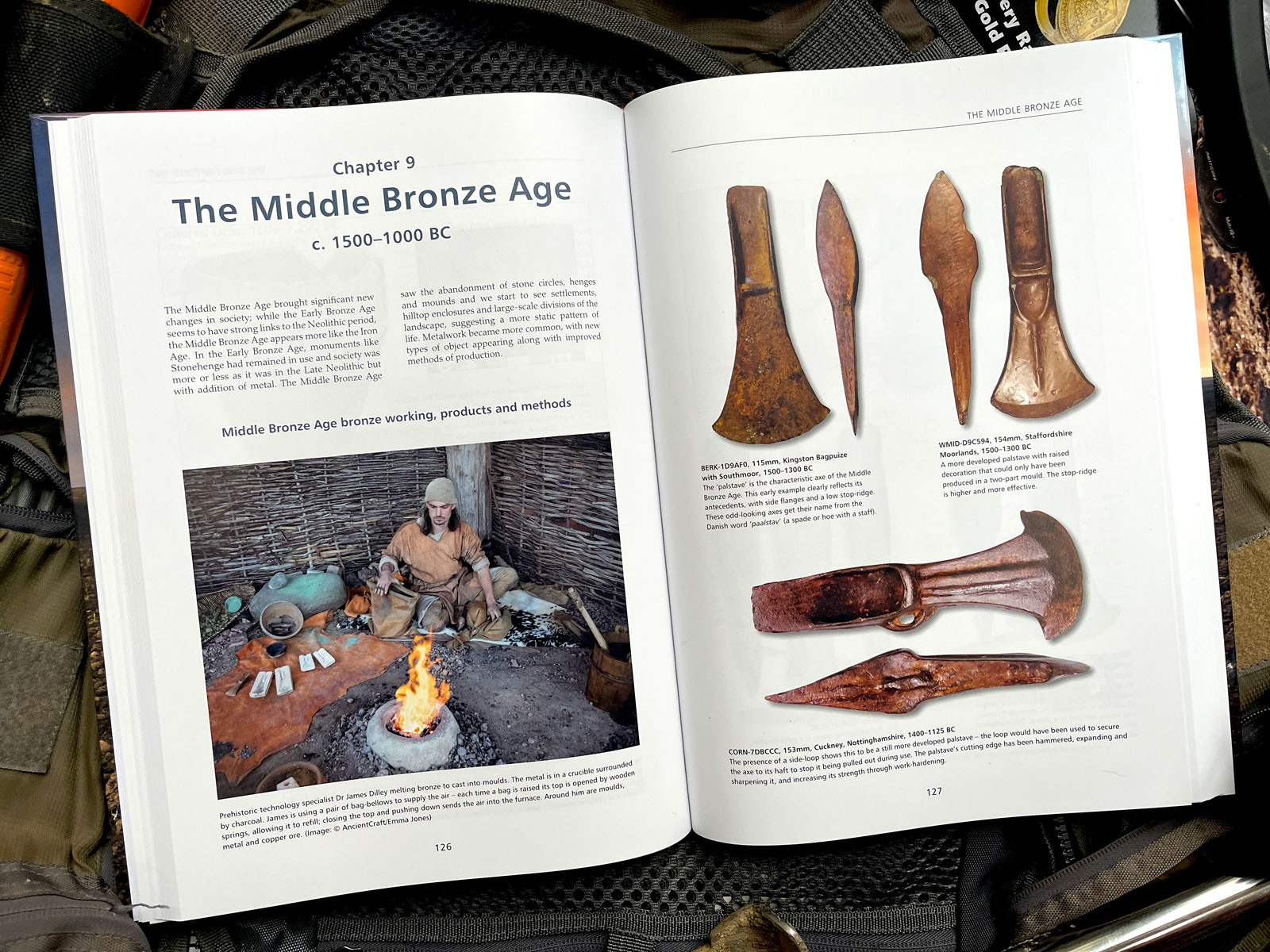

On the romans

My second port of call was the corner of one field where a rectangular enclosure had shown up on google earth and some of the aerial photography. Fortunately for me I am now also able to ask questions of Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews (the Curator and Heritage Access Officer at North Herts Museums) and Gilbert Burliegh (the retired archaeologist who oversaw the excavation of the Ashwell ‘Dea Senuna’ Hoard, and the once former boss of Keith). I showed the aerial photography to Gil and asked for his thoughts on what it might be which were as follows… “It looks like a Romano-British ditched enclosure, possibly originating in the late Iron Age”. It would turn out that his assumptions from looking at the aerial photography would be spot on!

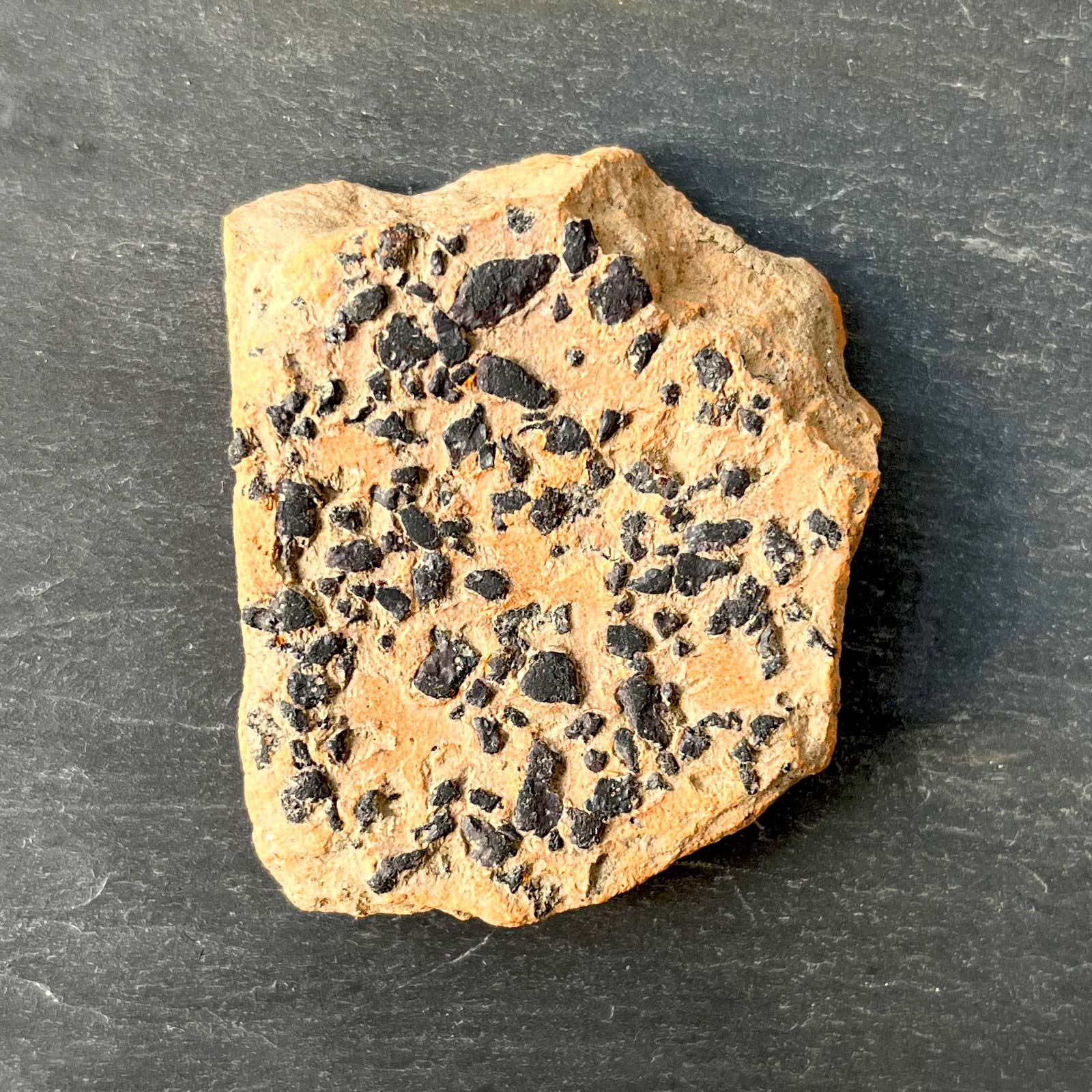

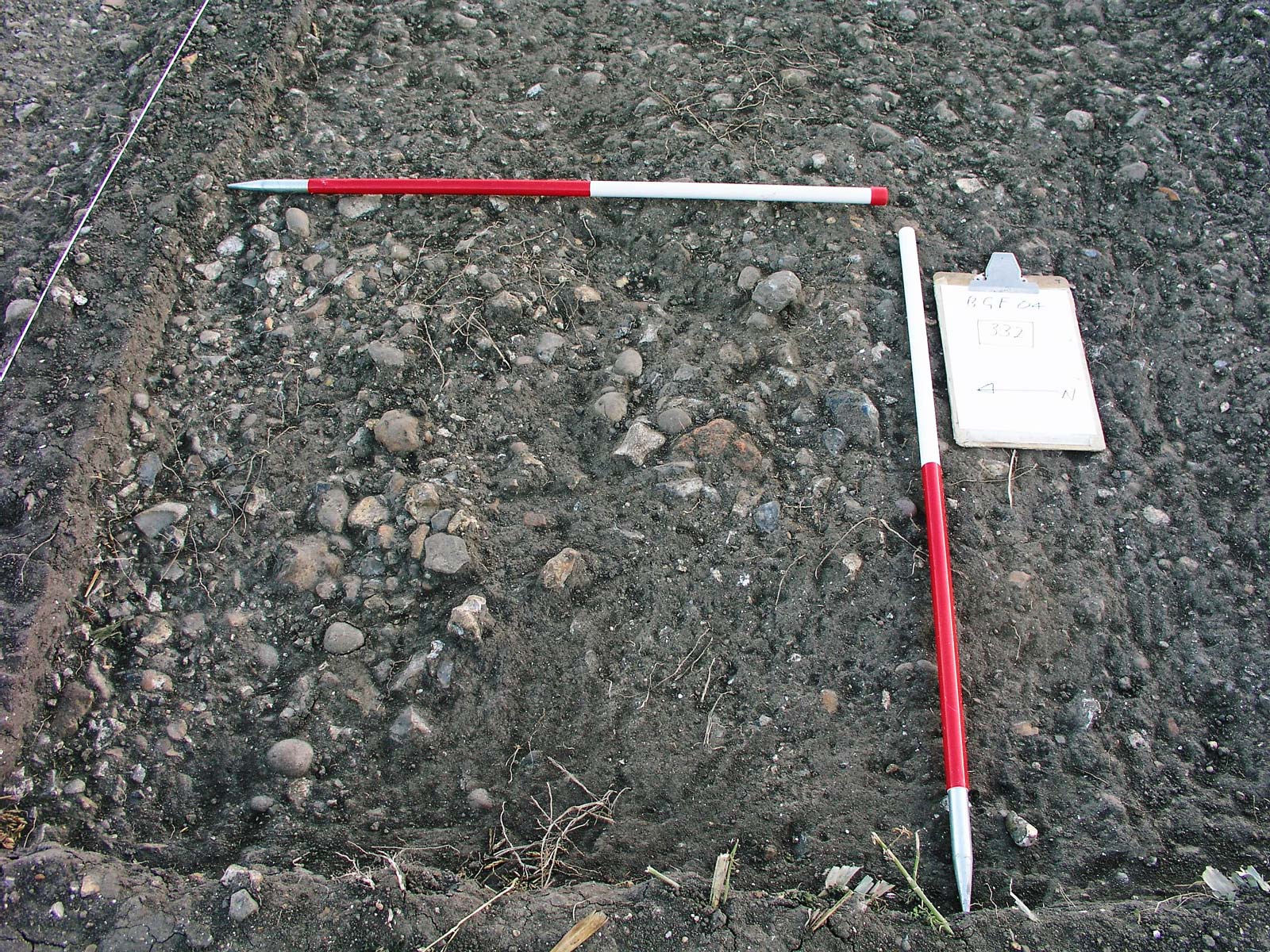

The first day on that corner of the field was cold but sunny and the green shoots of a crop had just started to push through (Fig.2). Even though this was the case it didn’t stop me from spotting pottery sherds scattered around, and lots of them (Fig.3). I messaged Keith to see if it was ok to pick some up to bring in to him to identify, which was fine as long as I provided the find spot locations as well. It turned out that most of it was Roman, but one sherd in particular was part of a mortarium (Fig.4), which in modern terms is part a mortar bowl with which we use a pestle to grind herbs and such. With all this pottery scattered about it wasn’t long before the Roman coins started to pop up. I had 12 Roman coins in all (Fig.5) and then rather pleasingly a Celtic Tasciovanos Verlamio bronze unit (20BC-10AD) turned up as well (Fig.6), which fits with Gil’s thoughts on the site perfectly, ten out of ten for Gil!

The silver denarius

Within the coins on Fig.5 you will notice that there is a silver denarius, which when I found it was a real heart stopping moment. The reason being is that the first side of the coin I saw was the reverse which carried the word Caesar (Fig.7a-7b). I can only think of one man when I see or hear the word Caesar and that is Julius Caesar. For a moment I was overwhelmed with finding a coin of one of the greatest historical figures ever known, until I sent a photo of it to Keith who immediately came back and said that it was his great nephew Octavian. But this was still impressive, to find a silver denarius from the Republic era and one which carried the head of Octavian who later became Augustus Caesar and founded the Roman Empire. This particular coin dates to the period AD 32-29 BC (RIC I 257, RSC I Augustus 61) and it is said to refer to the Battle of Naulochus. I mentioned this because the Battle of Naulochus took place on 3rd September 36BC, the date of which (excusing the year) is my birthday, how cool is that!

Towards the end of 2024 I attended a talk which Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews gave on the history of the local area, part of which was my permission. It turns out that the silver denarius of Octavian which I had found became a small feature of his presentation and Keith has kindly shared that part of his talk here.

“The discovery of a silver denarius of Octavian is unusual from an Iron Age to Romano-British farmstead. Its reverse legend Caesar Di(vi filius), ‘son of the deified Caesar’, shows the future emperor Augustus positioning himself as the rightful ruler of the Roman world around the time of his conflict with Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII for dominance.”

“Republican and early imperial denarii do sometimes turn up in Roman contexts in Britain: more than 2000 have been found. Some were brought in by the armies of invasion or circulated as part of the general introduction of Roman coinage, but others come from pre-Roman Late Iron Age sites. Some were imported to be melted down into coins struck by British rulers, including Tincomarus and Epillus of the Atrebates, while others were used as coins because their weight matched that of British coinage”.

Not a lot else came up on the site of this enclosure, but maybe more will turn up after the plough in a few years.

Across the road

This wasn’t the only site of interest that I had spotted in my research, on the other side of the road there were more rectangular features which needed my attention. Beyond the trees (Fig.8) was a huge field that had a lot going on in it and as always I was hopeful of finding lots of Roman goodies. The field I was stood in when I took the photo of the trees also had a rectangular feature in it but as yet I have not been able to detect there as it is currently occupied by a massive badgers set (Figs.9-10).

The bigger field beyond the trees didn’t produce the Roman bounty I was hoping for, but a few interesting things from various time periods were unearthed. There were a lot of finds from more modern times here, particularly buttons and coins as seen in Fig.11, but included in this shot is a small Celtic Unit (the toasted green nugget on the top of my finger). It wouldn’t be long before a few finds of a more significant variety would show themselves.

Two of those finds which I found on the same day were part of an Anglo-Saxon brooch, and a couple of broken fragments of a Roman Armilla bracelet (Figs.12-14). The pieces of Armilla don’t feature in the group shot (Fig.12) because they were in my scrap pocket at the time. It’s only when emptying my scrap pocket that I noticed the decoration which I recognised from a piece of Armilla which I found on another permission. When I showed these items to Gil, he replied with the following… “James, that is extremely significant. Armilla are associated with the Roman military in the 1st century AD. They are also associated with religious sites. Your site is shaping up to be very interesting indeed, not least because you have early pagan A-S evidence too”.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that the association of these bracelets with the Roman military is being questioned. Keith kindly steered me towards a PhD thesis authored by Dr Edwin Wood. Keith said “Something you may not be aware of is that Dr Edwin Wood has examined the distribution of so-called armillae in Britain in his PhD thesis and has discounted their military origin”. Keith continued to say “Interestingly, he compares their decoration with the recently-classified ‘Baldock torcs’ and with a particular type of nail cleaner associated with the town. I know that the interpretation of these bracelets as military is received wisdom and that anything supposedly associated with the Roman army gets people excited, but it might be good to throw out Wood’s significant doubts to a wider public”.

Another day in this field produced a few Roman coins and a beaten up silver hammered along with the usual buttons and modernish coins (Fig.15). But in the middle of all this was a piece copper alloy (which I assumed due to the green patina), and it was something that I had not seen before. This turned out to be part of a horse harness bridal bit (Fig.16) and I have just had it confirmed by FLO that it is from the Roman period. So with all the evidence that I have found so far in this short period of time, I think it’s safe to say that this area had been inhabited by the Celts, Romans and possibly the Anglo-Saxons, the picture these finds are building is starting to get interesting. It wasn’t long before this part of the permission was out of bounds due to the crops growing, but there were other parts of the permission still available.

The finds are scarce but still coming

I now moved to another part of the permission where things were looking quite busy on google earth. It was a section where there appeared to be lots of old boundaries all crossing over each other which shows up on multiple images on the google earth historical imagery time slider. This field was available for a couple of weeks so I made the most of the time, not a lot came up here but there was still evidence of Roman occupation. I found another piece of Roman mortarium (Fig.17) along with a copper alloy Nummus of Crispus Caesar (AD 317-326) (Figs.18a-18b), so the Romans were definitely around mixing their herbs and medicines.

Some more modern items showed up too including what I believe to be a book clasp (Fig.19) which was intricately decorated with Christian symbolism which conveys hope, faith and charity. I wonder if may have been part of a bible as there is a small village church just a stones throw from this field. Another day of detecting in this field produced my first complete silver spoon (Fig.20), albeit completely bent and twisted. But even so, the hallmarks were intact which told me that this spoon dated to 1804 and was made in London by William Ely & William Fearn, I wonder if there is a spoon missing from the family silver in one of the homes in the village, I’m sure someone got in trouble for that many years ago. You will also notice in Fig.20 a Roman coin at the top of my hand which has a hole in it, I assume because it was worn, possibly as a necklace? It’s something which features on a few of the Roman coins I have found here, so it seems it may have been a popular thing to do. It wasn’t long before this part of the permission was out of bounds too, so then onto the next part!

The roman road

This time I was heading into a field which my research showed had a Roman Road running right the way through it. In fact this road ran past the big Roman villa complex which was in the first article that I wrote about this permission way back in the September 2022 edition of Treasure Hunting Magazine. I also found out that a Geophysics survey had taken place on a cross section of this field by the Community Archaeology Geophysics Group (CAGG) which showed part of the Roman road, so I knew it was definitely there (Fig.21).

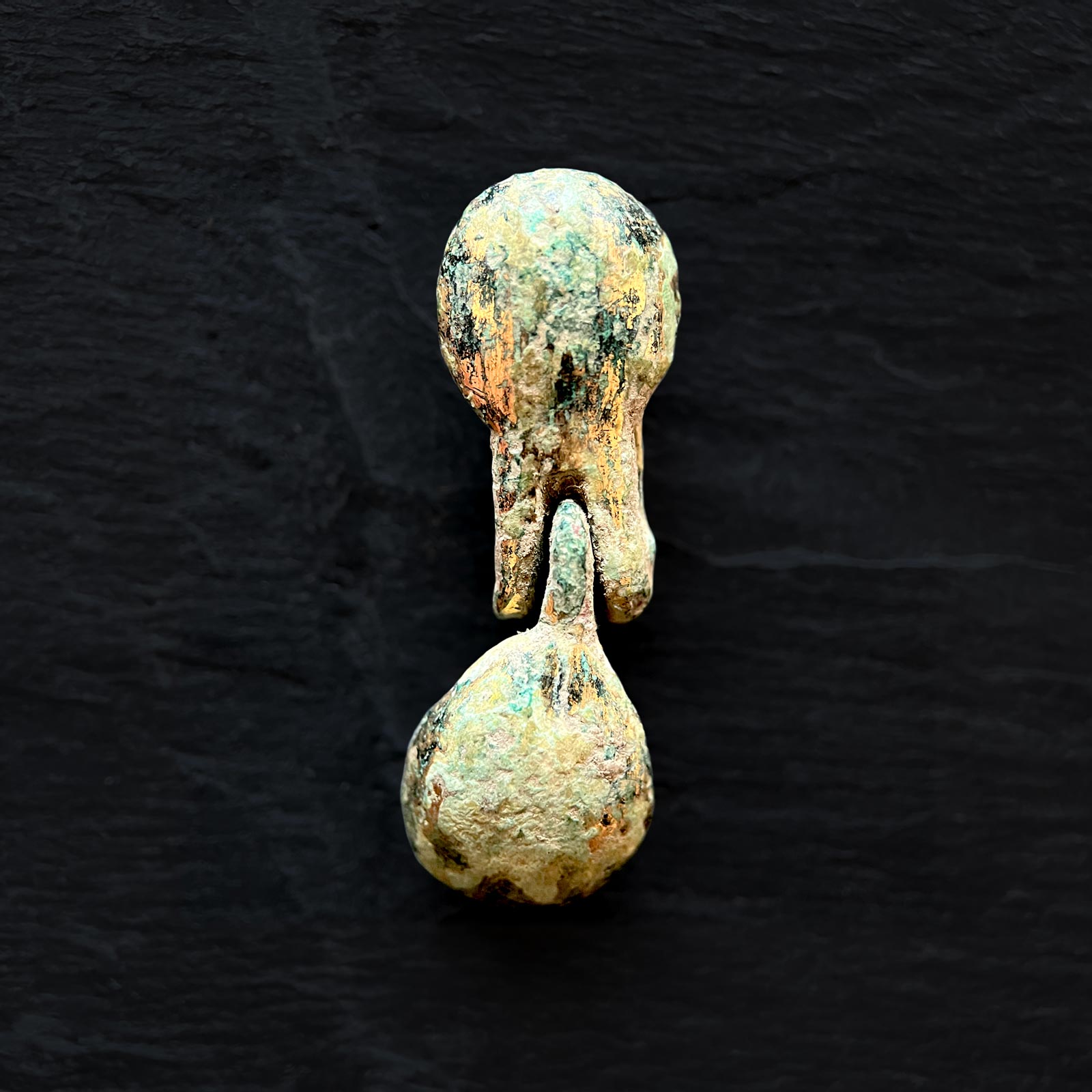

As you can imagine I was quite hopeful of finding some good Roman artefacts here, but again I didn’t have a huge amount of time before this field was out of bounds too. But on the few outings that I did have there were some nice finds as you can see in Fig.22. Amongst this lot was a corroded Dupondius of Vespasian (Fig.23) along with my first Roman brooch to come up from this permission (Fig.24-25), I believe this to be a Hod Hill type brooch which would date it to the 1st Century AD. None of these things are in particularly great condition, but they are all indications of the people who were travelling and living in his area which is one of the reasons why I enjoy this hobby so much. Another little item which came out of this field was a cloth seal from the 1700’s (Fig.26-27). This one depicted the head of Queen Anne (1702-1707) and on the reverse has a rearing unicorn with the number 3, which was its subsidy value of 3p. I was quite chuffed with this little find as lead times from this period don’t usually fair so well in the ground.

Another first came up in this field which I thought was just a worn out silver sixpence (Fig.28), but curiously I noticed some stamp marks on one side. I decided to post this on a detecting Facebook page and one member came back with the following info. “Originally a William III sixpence, very late 1600’s, then later on re-used in the late 1700’s, early to mid 1800’s. They were counter marked commonly by Irish workers as they are known in the detecting world as “Irish slap tokens”. This is another great aspect of the hobby, which is people are willing to share the their knowledge, you learn something new everyday, eh.

My first treasure case

The slap token was the last find before moving onto the next part of the permission which was literally just over the hedge from this field. This was actually two fields and again I wasn’t going to have long to search them, in actual fact over two weekends I spent two afternoons on them. I will cut to the chase on this part of the permission because most of what came up was scrap pocket fodder, apart from the three lovely items in Fig.29. I’m sure most readers will recognise the broken Edward I penny and the threepence of Elizabeth I, but the third item is new one on me, is it on you?

This pretty little bouquet (Fig.30-31) turned out to be my first treasure case would you believe, and what follows is the summary of the find from the British Museum. “An incomplete Post Medieval silver gilt dress-hook dating c. AD 1500-1600. Read’s Class D, type 6. The dress-hook consists of a trefoil shaped plate with petaled edges and separate soldered transverse attachment loop. The separate soldered wire hook is missing, leaving traces of solder”.

It was pretty cool to have my first treasure case go through, but it did amaze me that this little thing constituted as treasure. I had it in my head that treasure meant vast hoards of gold and silver, not a broken dress hook. Still, a nice little find none the less which all adds to my experiences of being a detectorist.

A deserted medieval village

Now I’m finally getting closer to where I want to be, the site of a deserted medieval village. I will be honest, as much as I did want to detect on this part of the permission I wasn’t too hopeful of finding that much as the village had been extensively excavated by archaeologists the 1970’s. Since then I believe a fair few detectorists have covered the area over the years but to my surprise a few nice things came up. These included a broken part of a medieval zoomorphic vessel handle (Fig.32), a hammered Half penny of King Henry V (Fig.33), a crotal bell which was a ringer (Fig.34) and another zoomorphic end of a medieval pot handle (Fig.35). There was also plenty of general detecting pocket fodder as seen in fig.36.

Meeting new friends

It was also around this time that I met another detectorist called ‘Dal’ out in the field who also had permission on this land. Weirdly we had been following and chatting to each other on instagram for about a year or so not knowing we shared the same permission. Since then we have been out a few times together with varied results. The first time we met was at the end of one of my sessions where I had found a mass of buttons as seen in fig.37, he on the other hand had just found a Roman finger ring, not precious metal and broken but still a bloody good find.

The last time we went out it was my turn to have the find of the day. But before I get to that, I found out that during the excavations of the medieval village in the 1970’s, the archaeologists were a little puzzled that they had bits of Roman and Celtic archaeology turning up here and there. It now transpires that with the help of aerial photography it looks like there was a Roman settlement of some kind in the same field, which probably started life in the late Iron Age. Well, with the next set of finds I would say that’s a strong possibility.

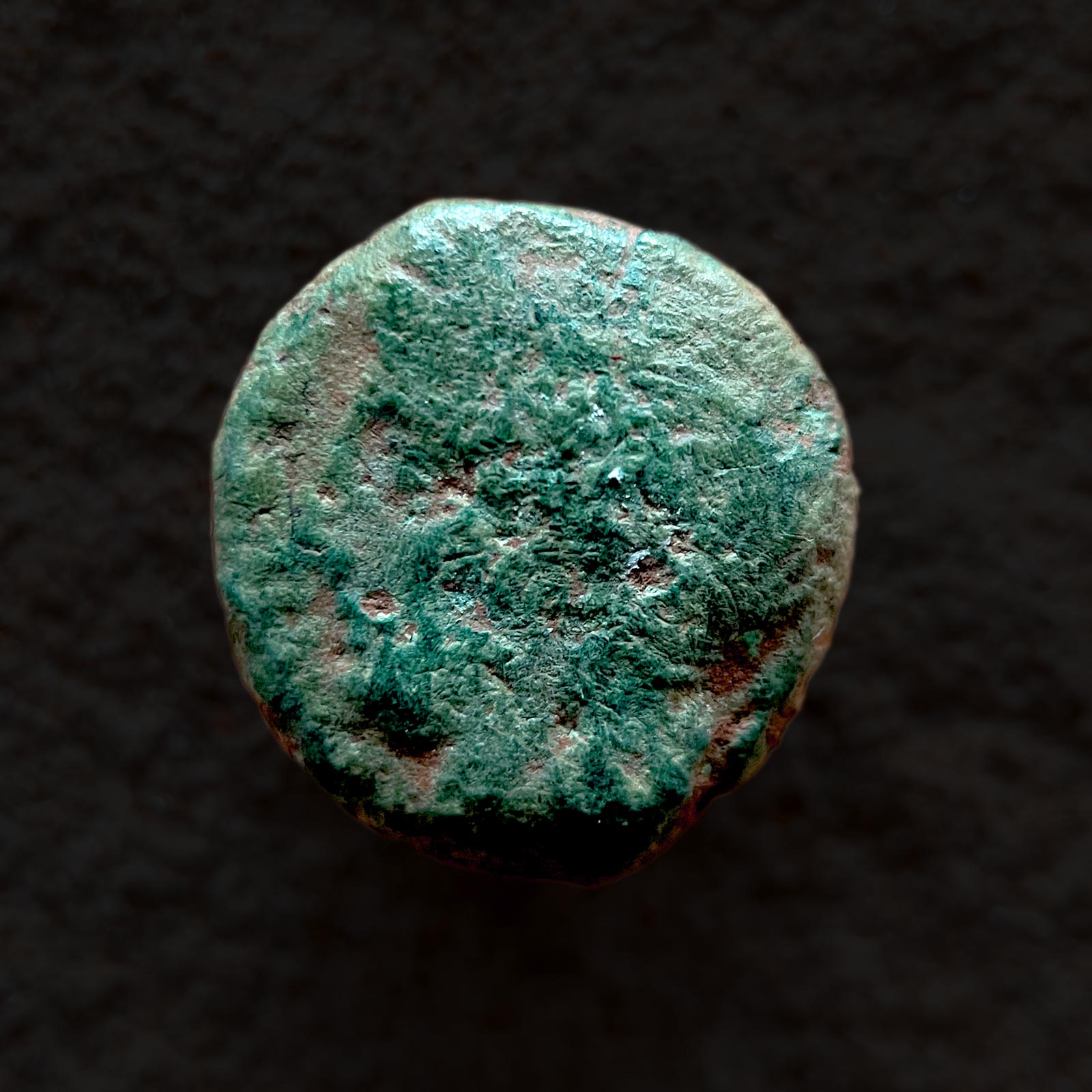

The Romans and the Celts

Finally I was in the field I had been longing to get into, it hadn’t been possible before now because a crop had been in for quite sometime, but now it was coming out. Even better than that the field was being deep ploughed so hopefully new finds were being brought up to the surface! We had a morning on the field before we were told we couldn’t have anymore time as another crop was going straight in, which as you can imagine was incredibly disappointing. But the handful of stuff I did find (Fig.38) in those few hours gave me a glimpse of the history that was potentially there. In that handful of stuff was a beaten up Celtic bronze unit (Fig.39) which had just enough left on it for me to identify. This barnacle encrusted morsel is actually a bronze unit of Cunobelinus which dates 10-40 AD, so the Celts were here, now what about the Romans?

Well, on another trip out on this field we were allowed to go over one corner where the sugar beat crop had been stored. Now the crop had been moved we were free to give that little area the once over. To my surprise just lying on the surface was this belter of a Silver Denarius with the face of Hadrian just starring back at me (Fig40a-40b). The coin dates to 133-135AD, and depicted on the reverse is Salus, the Roman Goddess for wellbeing and safety. It was my eye that caught a flash of silver first but my detector confirmed the fact. But I did wonder why it was just lying on the surface and it now occurs to me that it must have come up with the beats and then fallen off as they were being moved to storage. This quite rightly suggests (I think) that this coin has come from another part of the field, but where?

Roman detail

The detail on this coin as seen in Fig.41 is pretty much in mint condition, which might mean it’s part of a larger collection of coins that were all buried here before they were used. Lol, that’s just me fantasising about finding my first hoard, but who knows, maybe this coin does have a few brothers waiting to be found. At the very least these finds go someway to confirming the origins of a possible Romano-British settlement, which is further supported by Dal finding a Roman disc brooch with some glass decoration and gilt still intact.

Time for a memoir?

It’s going to be while before we can get back into this field but it’s great to know that there is the potential for more finds to be found. It can be frustrating the amount of time us detectorists have to wait to sometimes get into certain fields, but I find it does leave time for other pursuits like writing these articles which is also a great part of the hobby for me. Maybe one day I will be able to write my detecting memoir just like Julian Evan-Hart has done, although mine would probably be better titled as ‘My Detecting Strife’.

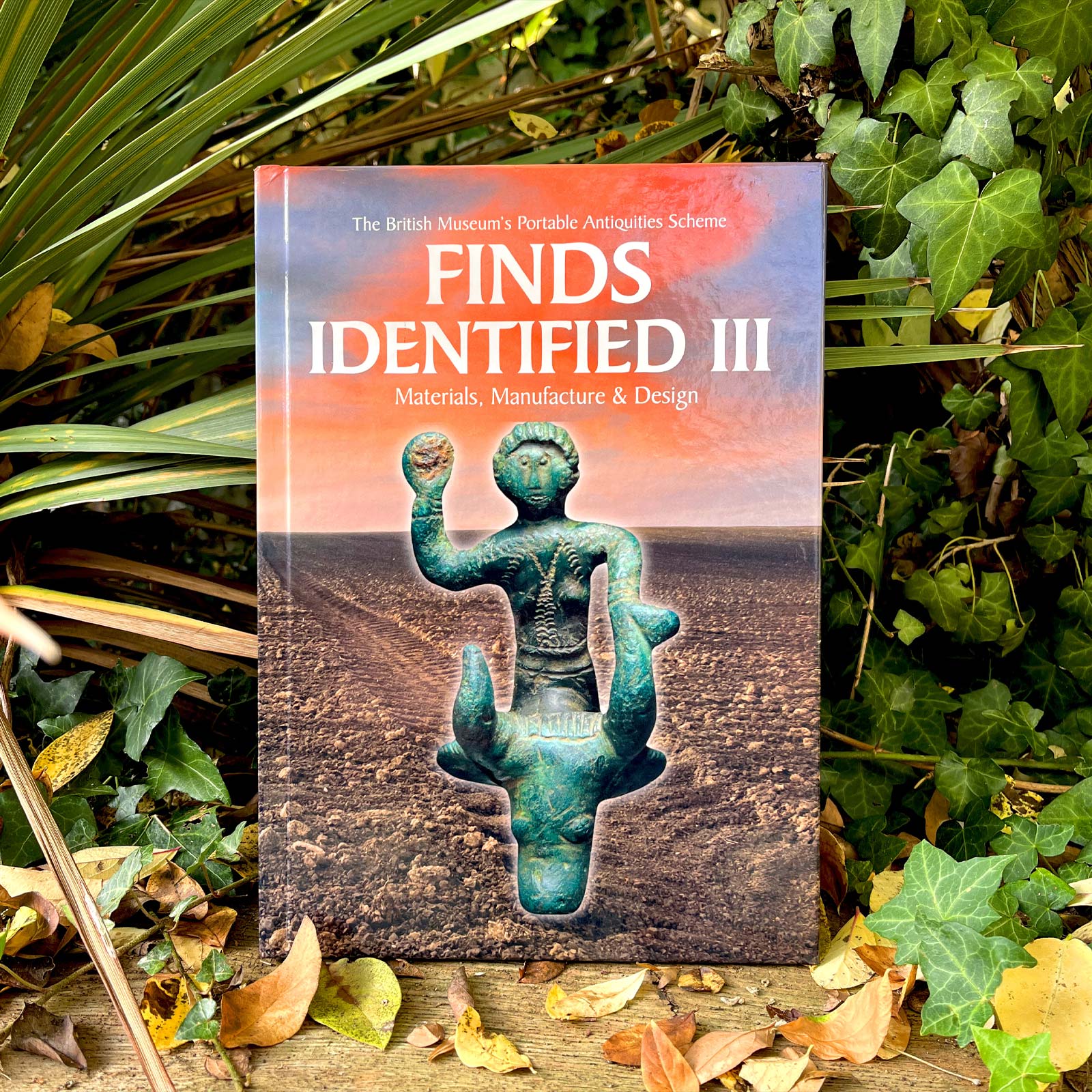

Finds identified III

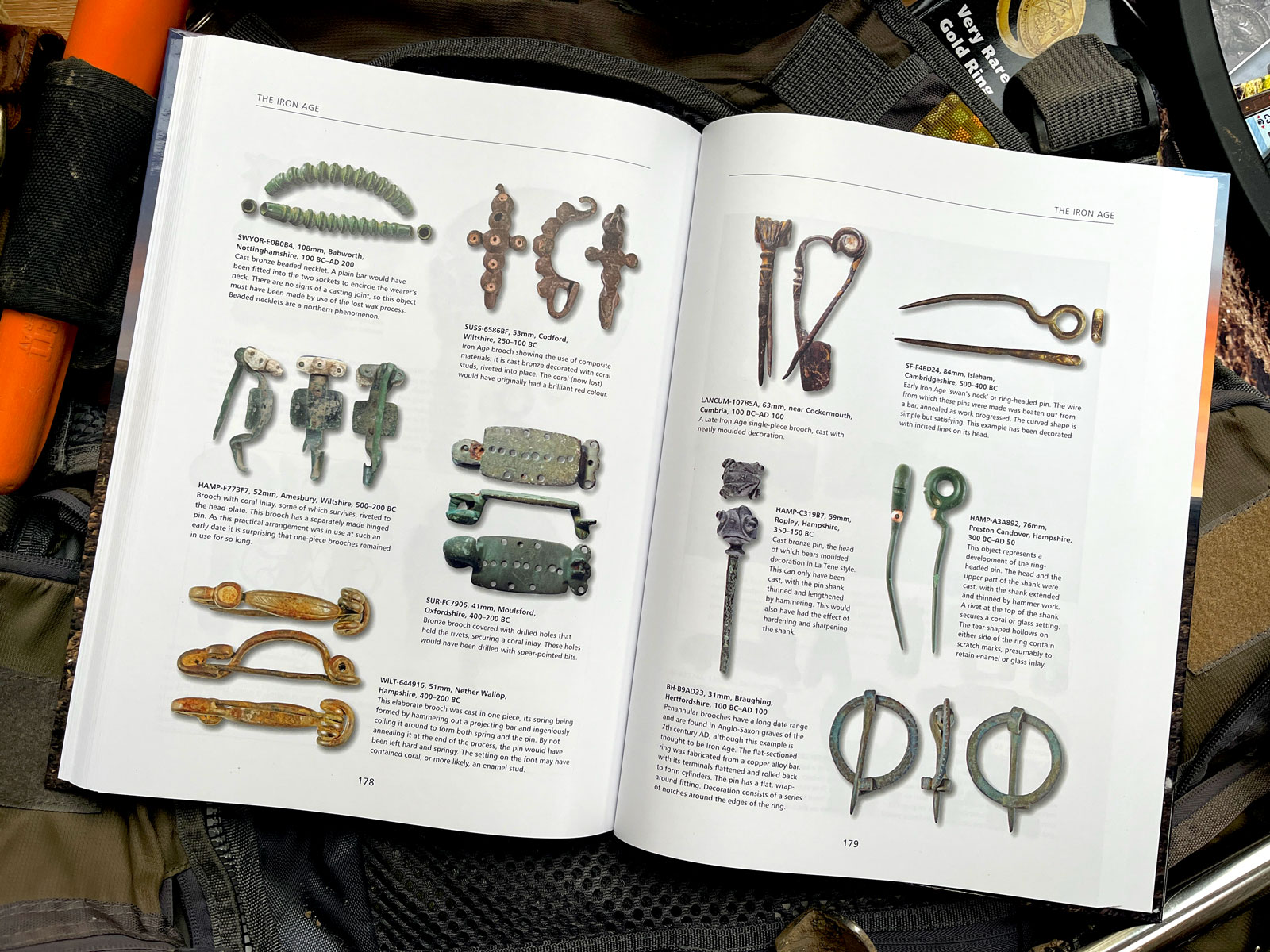

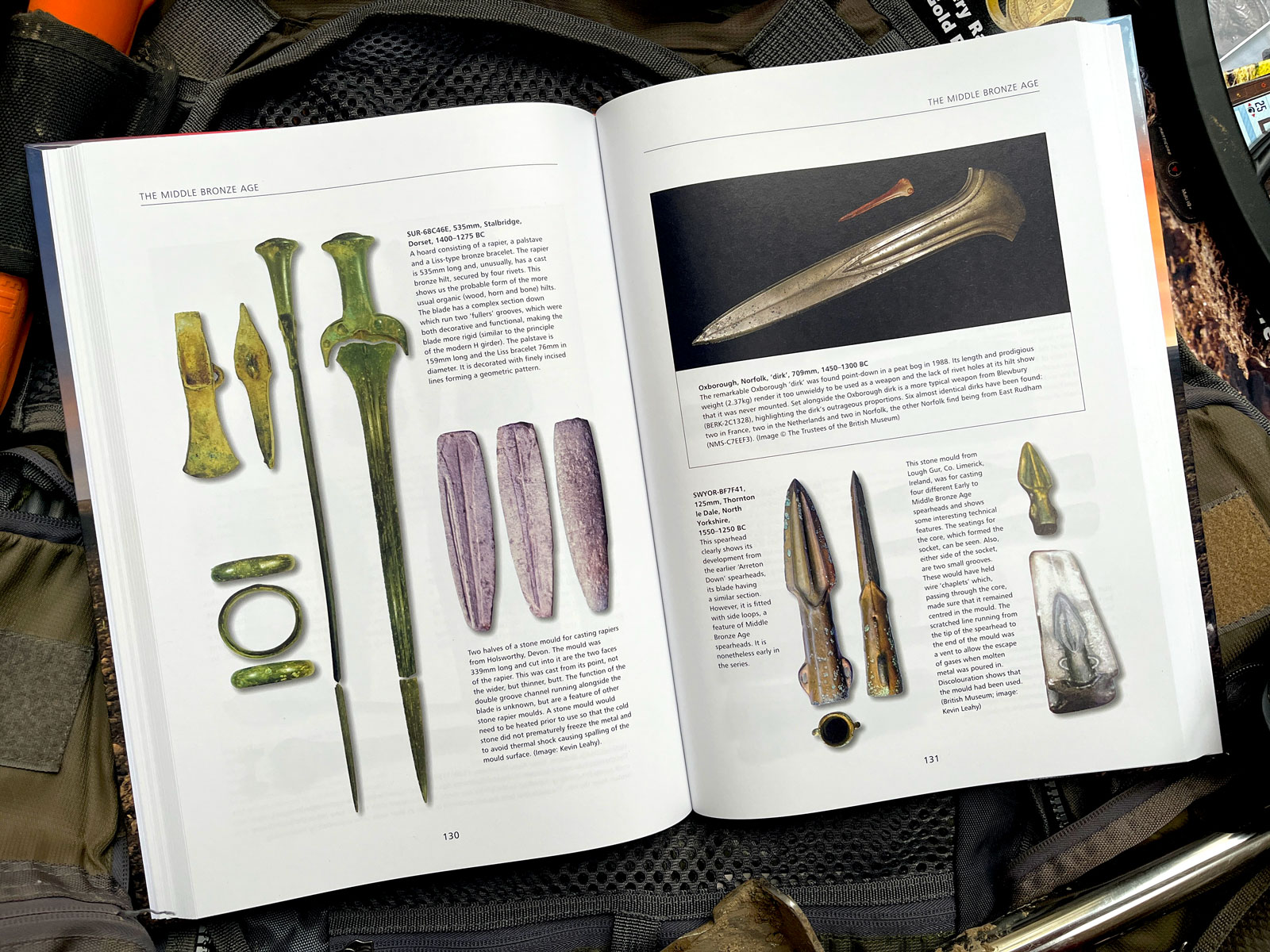

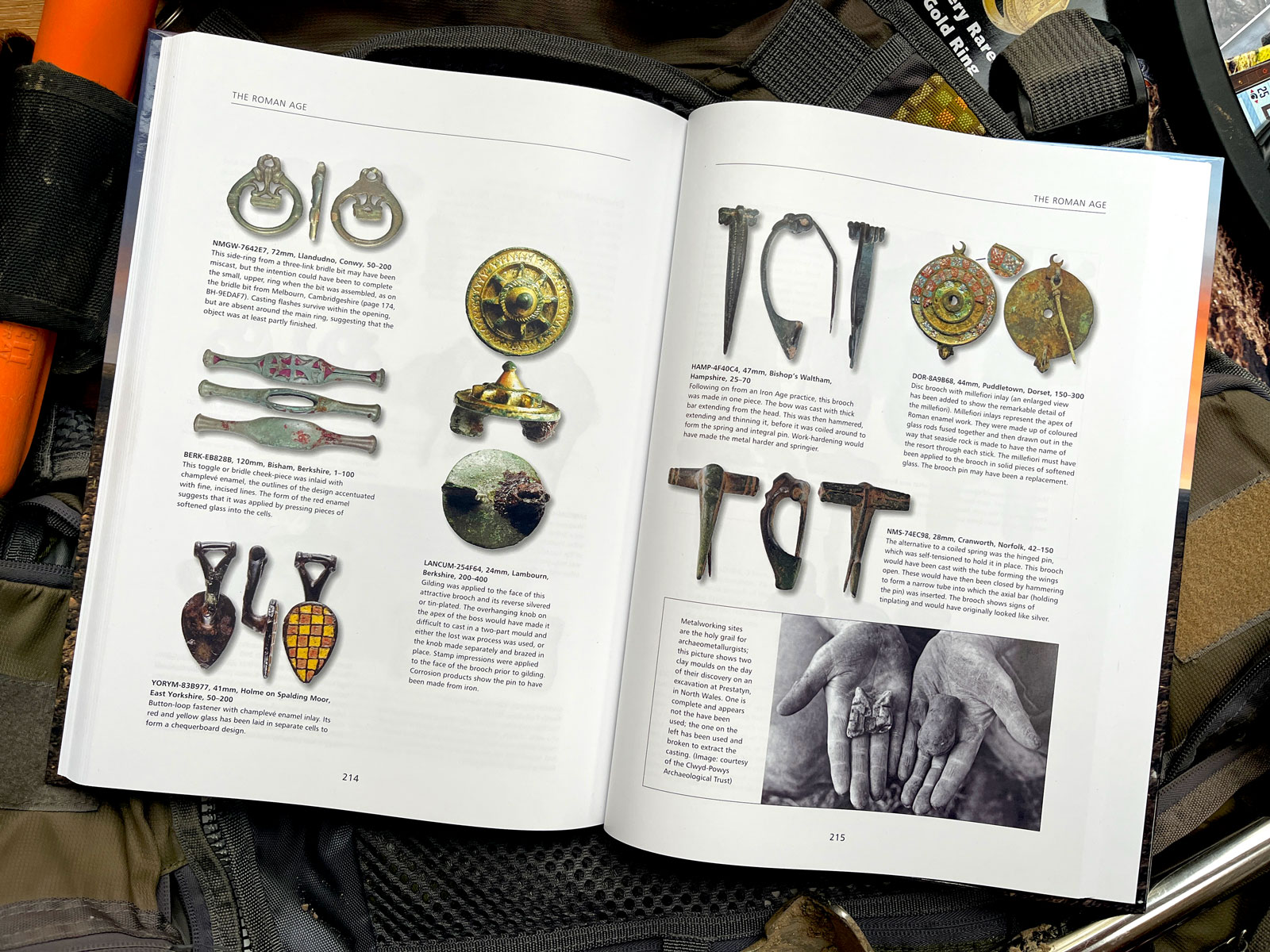

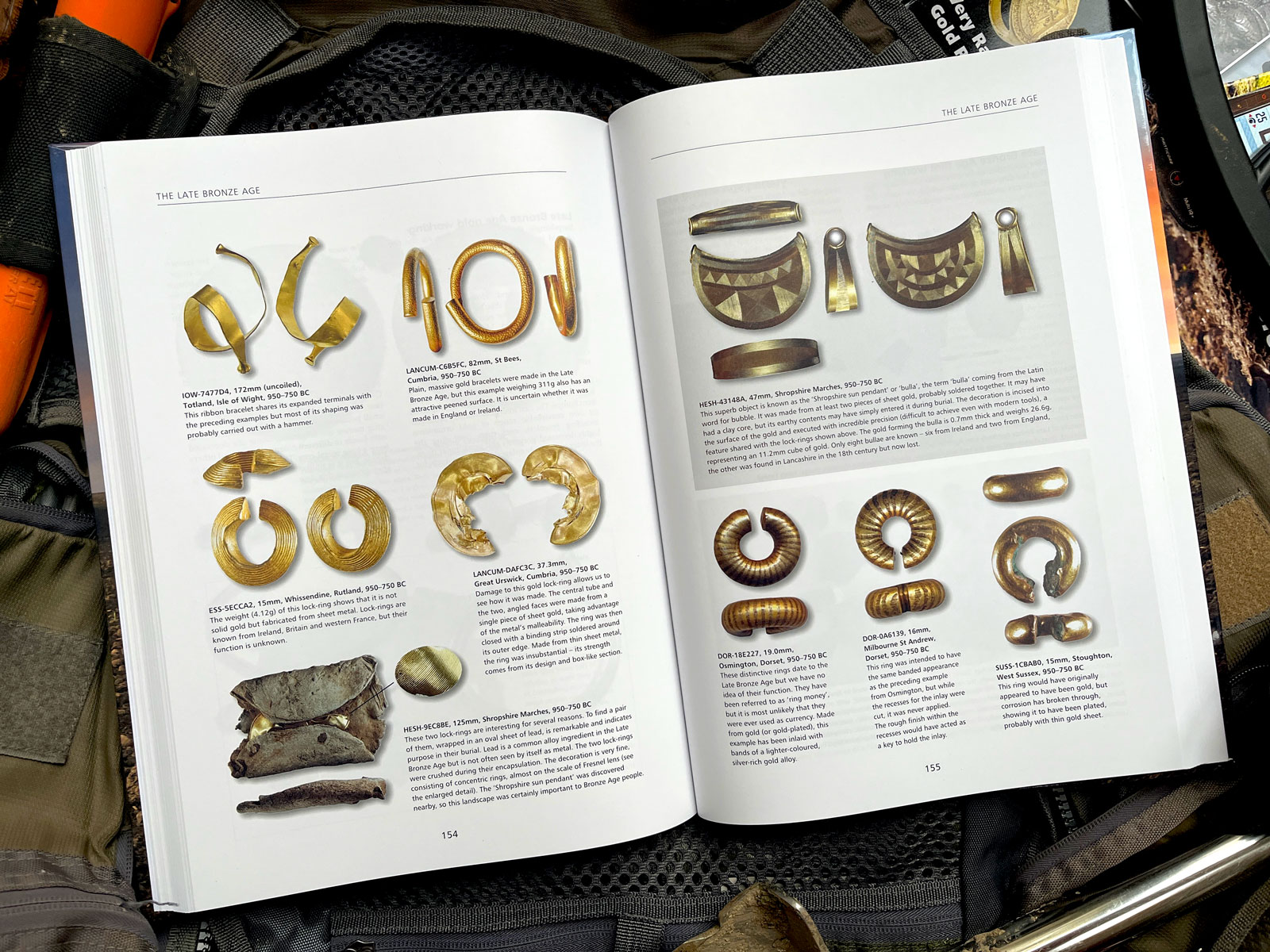

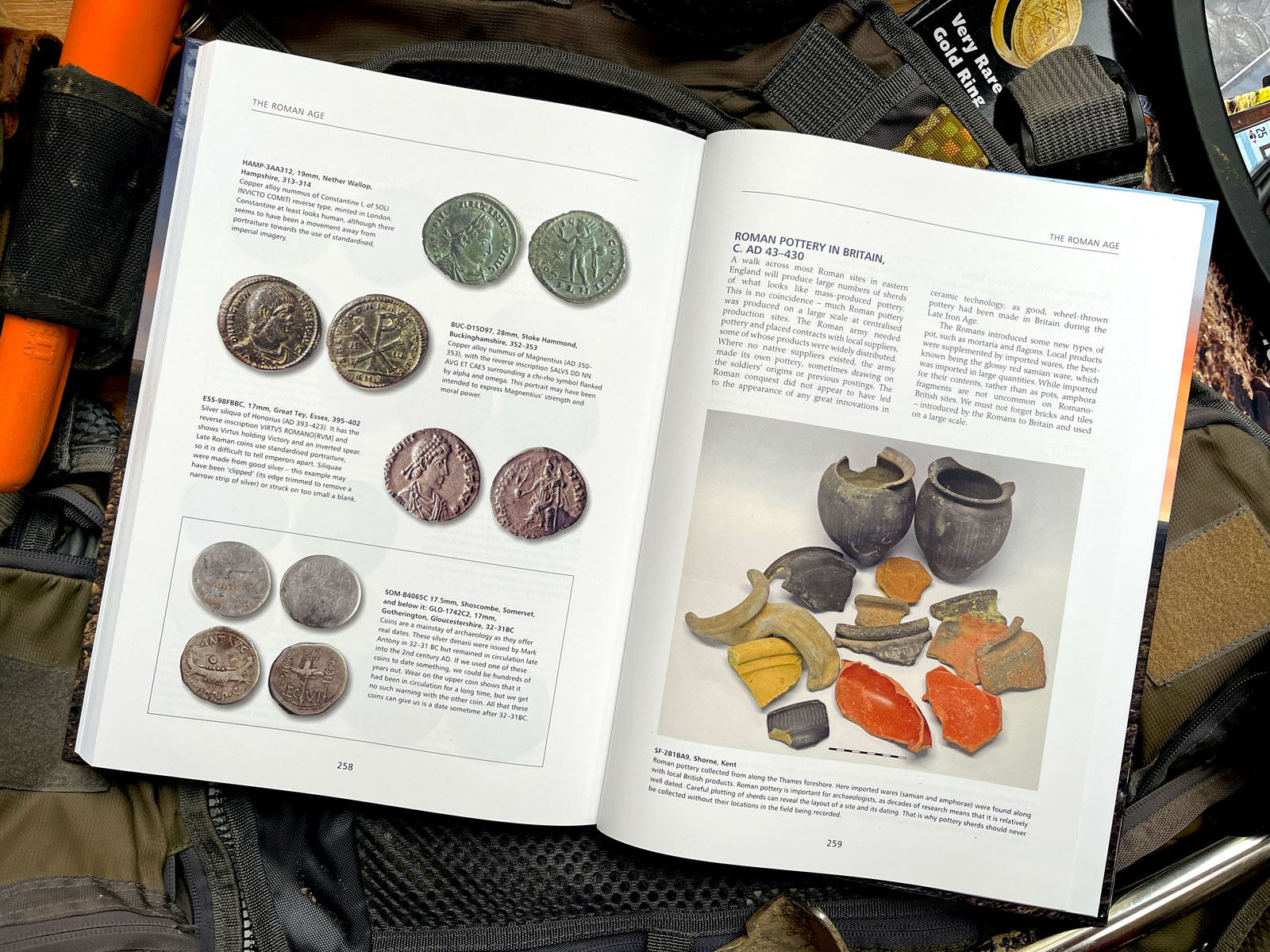

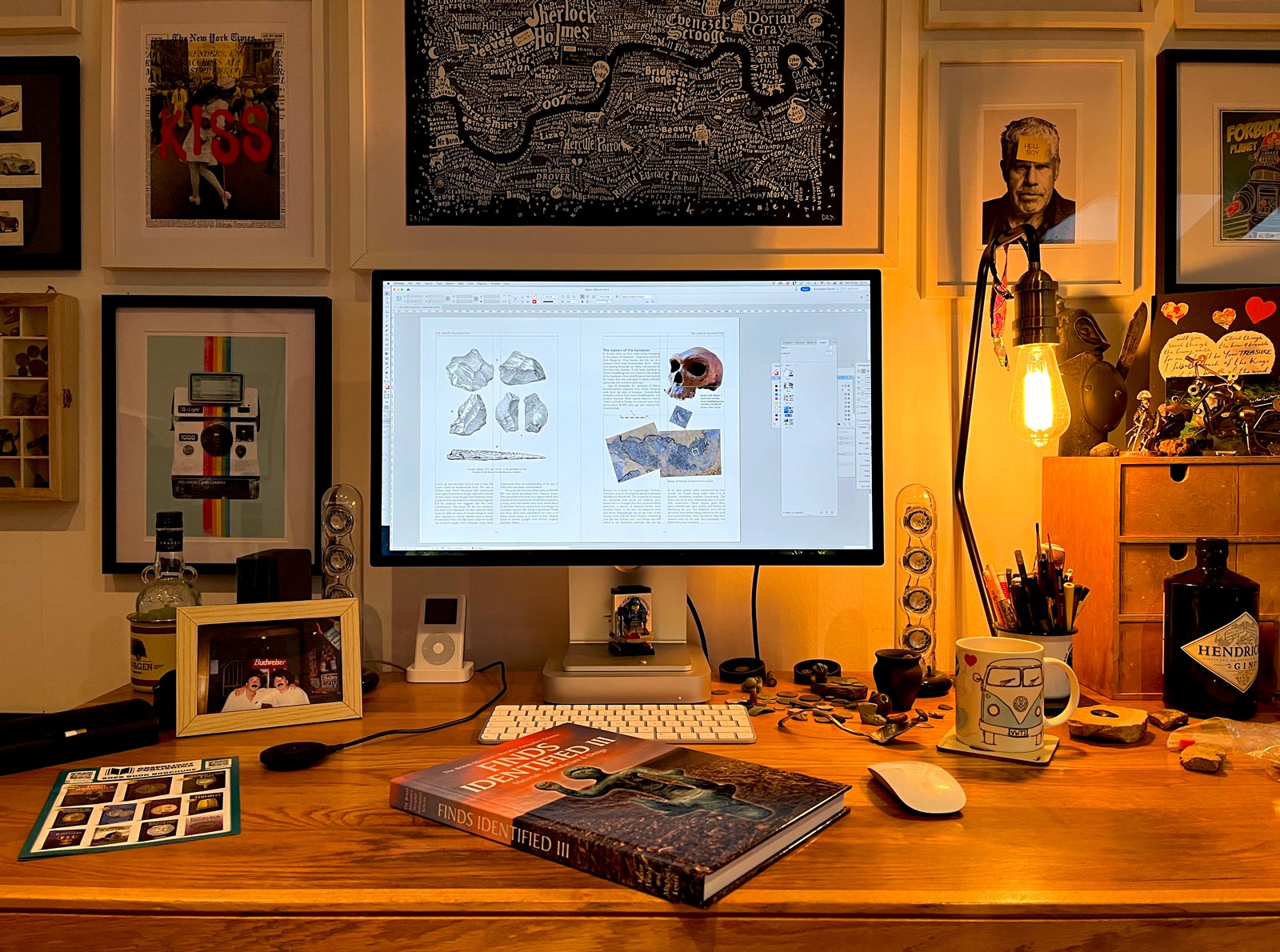

Back in May I wrote a blog titled ‘detecting, writing & work’ in which I talked about helping the team at Treasure Hunting with the layout for the May and June issues of the magazine. Having helped out on previous issues when they were busy, I was more than happy to do so again whilst they looked for a new artworker to take on the job as a permanent role. Once the Treasure Hunting team found their new artworker I thought that would be the end of my involvement for the year. But a few weeks after I finished my stint on the magazine the Treasure Hunting team contacted me again. This time they asked if I would like to design the layout for the third instalment of The Portable Antiquities Scheme’s ‘Finds Identified’ series. Being a big fan of these books I jumped at the chance of putting the third edition together.

Laying out a book like this is quite a time consuming affair as it’s basically a big jigsaw puzzle with no instructions on how it should fit together. At the start I was provided with the artwork from the previous edition which gave me access to the fonts and styles so the third book would be in keeping with the rest of the series. Then I was given the new text and imagery and from there it was my job to make the book flow well and look good. It was definitely a task that required forward planning as I needed to ensure that every chapter (apart from the first) started on a left hand page. This makes it easier for the reader to identify the beginning of each chapter, and it looks better from a design point of view.

To ensure this worked, I roughly layed out each chapter page by page with the relevant text and images. At this early stage I was also working out which items would benefit from being highlighted or sectioned off to give the book design more interest. There were also several sections of information which needed to be kept together as spreads rather than split over one leaf, so these were design considerations that also required careful planning. Working in this way enabled me to ensure that each chapter started on a left hand page before committing the time to making the book look good from a design perspective. This also made it easier to ensure that each chapter flowed well from page to page making it an enjoyable experience for the reader. The only aspect of the book which didn’t have my input was the cover, on which I have noticed a small anomaly. I’m sure it’s something that most people wouldn’t notice but my design eye spotted it straight away. For some reason the white shadow around the figurine has been slightly cut off above the head, a little thing but a niggle nonetheless. But I have since noticed a couple of small things within the book which are little irritations of my own making, there’s always something.

After spending many an hour making sure all the pieces of this jigsaw slotted together well and looked good, the puzzle of Finds Identified III was finally finished, and I think it has turned out pretty well. On the final corrections correspondence one of the authors, Kevin Leahy, commented that I had ‘done a great job’, which for me was the icing on the cake, as I’m immensely proud to have been a part of this project. Being a passionate detectorist myself makes it all the more special to have my name in the credits of a book which is loved by both the detecting, and archaeological communities alike.

Another reason I feel privileged to have worked on this book is because most of the finds within these pages have been found by detectorists like me. Not only does this highlight the importance of reporting finds to the Portable Antiquities Scheme, but it’s a testament to the amazing contribution that the detecting community has made by discovering and recording our buried past. Without our endless hours of wondering the British countryside we wouldn’t have these brilliant books, or the PAS database to use as reference for identifying our finds. So to every detectorist who happens to read this little blog, I salute you!

Lastly I would like to thank the guys at Treasure Hunting Magazine and Greenlight Publishing for letting me loose on Finds Identified III. I have thoroughly enjoyed the process and hopefully this won’t be the last time that my name appears on the credits to one of these fabulous books. 🙂

Another 100 acres

As we all know one of the most frustrating and difficult aspects of this hobby is obtaining permissions. It’s because of this that I feel incredibly lucky to have access to some brilliant permissions, one of which I have already written a couple of articles about at Weston in Hertfordshire. Last year around spring time it was getting close to the point where the fields at Weston would be seeded and detecting there would finish for a few months. It was on the last day of detecting that the landowner came out for a chat, and just as he was about to depart he dropped this bombshell of a line, “oh, did I mention that I have another 100 acres down the road?”.

A long wait

Wow, I couldn’t believe our luck, I say our as Weston is a permission that an old school mate and myself share together. Like Weston at this point, we wouldn’t have access to these new fields until the end of the harvest, so now we had a few months of imagining what could be out in these new fields. The time eventually came when there was a gap between harvesting and seeding so we had the chance to go out for a few days before we had proper access at the end of summer. This gave us a tantalising taste of what could potentially be lurking beneath the earth.

Between finding out about the permission and physically having the chance to get out there gave me plenty of time to do some research on the area. This brought to light some really interesting features which included a possible Roman farmstead and a large Iron Age enclosure. Having to wait a few months imagining what might be there was hard, and anyone who is as passionate about this hobby as I am will understand what I mean.

The first two days

The first of two days out on this permission produced a couple of promising finds, both of them being Roman coins. The first was a very worn coin which has been described on the Portable Antiquities Scheme as follows… “A worn Roman copper-alloy dupondius of an uncertain emperor dating to the period AD 1-250. Unclear reverse depicting a standing figure, SC across fields. Mint of Rome” (Fig.1). The second coin was a big improvement and it’s the third silver denarius that I have found on my detecting journey so far (Figs.2a & b). This coin depicts Emperor Antonius Pius (AD 138-161), and even though his nose was missing and there was a few blemishes on the reverse it was a brilliant coin to find. On a slight tangent, I think back to when I was a kid in the eighties going to the local newsagent to buy a pack of Panini football stickers. I would carefully tear the wrapper in the hope of seeing a bit of silver that would indicate a team badge (also known as a shiny, those of a certain age would get this reference). It’s a bit like that with the Roman coins when me and my mate are on the permission together. On finding a Roman coin one of us would shout “Roman”, and the other would automatically reply “Sliver?”, and usually the answer would be “Nah, grot!”, but not on this occasion, this was a shiny!

Winter is coming

After those two days it would be another month before we were back out on these fields, but at least this meant we had the whole permission over the autumn and winter months. The permission itself is effectively split in two by a small river, and when I say small, it’s now barely a stream. Many centuries ago It would have been more like a river and was probably navigable as the water table in this area would have been higher back then. This may explain why the two enclosures I could see on google earth were quite close to the river. Both enclosures were on the same side of the river and on the other side there was nothing really of note, and it was the same with the finds. Pretty much everything you see in the pictures accompanying this article were found on the side with the two enclosures. But all of the finds you see here were few and far between, it’s taken a lot of walking to find this lot, and we’re talking Lands End to John O’Groats kind of walking!

Detected before?

The fact that the finds were few and far between got me wondering if this permission had been detected on before. The landowner purchased these fields 7 years ago during which time he hasn’t given permission to detect here. Before that I have no idea of what the metal detecting history of these field are, but the fact that not a huge amount has come up here and considering the two enclosures that I mentioned makes me think I’m not the first to detect here. I subsequently found out that the route of a Roman road ran right between the two features, so surely there must have been more here than what I have found? Still, a few of the things that I have found here have been pretty special.

So many buttons

As I have just mentioned the lack of finds did make me wonder about the detecting history of these fields, and I still think I’m not the first to detect here. But there was a strange anomaly on one section of the permission which was red hot with finds, a hot spot if you will. Buttons, bloody buttons, buttons, buttons, they were just everywhere in this part of the field. As you can see in Fig.3, this day was a button day and most of them were military buttons, and even now if I go to that part of the permission I can guarantee a button will come up. This does make me think that if other detectorists had been here, then surely they would have hoovered up all of these buttons? The presence of these buttons are probably the result of old World War military uniforms being dumped and ploughed into the land, something that did use to happen, much like the farmers plough in green waste today (which is a big problem to be discussed in another article). Still, all these buttons did give me hope that there would be sections of this permission that would have been missed if other detectorists had been here.

Silver and gold

As well as the denarius I found, a few other silver coins have shown their faces here too. These include sixpences, shillings and a splattering of hammered coins which can be seen with a myriad of other finds in Figs.4-8. I also found my first Elizabeth I hammered coin, a sixpence which can be seen in Fig.9a & b. But most importantly this permission is where I found my first gold. I have no doubt you will agree that this is a pivotal moment for every detectorist, being able to dance that fabled dance is a magical thing to be sure! This find came in the form of a gypsy ring (Figs.10-12) which was 18ct gold set with two rubies and a diamond. From the hallmarks I was able to decipher that the ring was made in Birmingham in the year 1897. It wasn’t particularly valuable as the ring itself had sustained some damage, but it was definitely a moment that I will never forget, a detecting right of passage ticked off the list.

Things of significance

A few other bucket listers came from this permission the first being a medieval horse harness pendant (Fig.13), something I had been wanting to find for quite a while. The pendant was quite beaten by the sands of time but it wasn’t broken. The face of the pendant is decorated with rampant lion facing left with a forked tail in raised relief and a small amount of red enamel on the outline survives. The second bucket lister was a silver Commonwealth halfgroat (Fig14a & b). These coins were minted in the period 1649-60 when there was no monarch as Charles I had been beheaded and Oliver Cromwell took power, which is why these coins were produced without a royal bust. Commonwealth coins from this period are not common finds and this little chap was just lying on the surface sunbathing.

It’s not often that you find lead items in good condition so I was quite surprised when a couple of lead seal matrix’s came out of the ground (Figs.15 & 16). Both are medieval and have been dated to the period 1200-1400. These two were found quite close to the rivers edge near to where the Roman road must have had a bridge or ford of some sort so people could cross over. I wonder if these items belonged to travellers who stopped at the riverside for a break and a drink and then lost them before carrying on their journey. Again it’s something we can only speculate at, but these lost items always make me wonder how they came to be lost, and more important how much they were missed.

Another significant find was a section of Roman Armilla bracelet (Figs.17-19), which despite being broken was in really good condition. I almost through this in my scrap pocket until I wiped away the earth and saw the decoration. I showed this section of bracelet to the now retired archaeologist Gilbert Burleigh, who was the subject of my last article.

Gil responded with the following “James, that is extremely significant. They are associated with the Roman military in the 1st century AD. They are also associated with religious sites. I’ll send you what I wrote about armilla in my PhD text”.

The following is the extract from Gil’s PHD text. “On the other hand, traces of an enigmatic military presence have been found in the form of a small-number of military dress fittings, especially in the vicinity of the ritually-used doline on BAL-1 (cf. the military finds from the ritual ceremonial hollow at Ashwell End; Jackson and Burleigh 2018, 214 & 285-90, figs. 332-5). One of the military finds from Ashwell End was a distinctive type of bracelet. This distinctive type of wide strip penannular bracelet with transverse decorative panels at the terminals has been convincingly identified as a male accoutrement, a type of military armilla awarded to soldiers in the early stages of the Roman Conquest of Britain (Crummy 2005). Distributed in the south and especially the east of England there are particular concentrations in Essex and Hertfordshire and, significantly, examples from the Harlow temple site, the Hockwold cum Wilton sanctuary sites at Leylands Farm and Sawbench (ibid., fig. 2, tables 1–2, cat. nos 11, 29 & 30), and from the religious site at Springhead, Kent (Schuster 2011, 235–6, fig. 100, nos 145–6). But the closest parallels to the Ashwell bracelet are two examples from Stead’s Baldock excavations (one from Site A, pit 405, near the Wynn Close shrine enclosure), with exactly the same décor on hoop and terminal, one of which was found in a context dated AD 50–70. The other was found on the Telephone Exchange site in 1969, not far from the Romano-Celtic temple on Baker’s Close, the other side of Clothall Road (Stead and Rigby 1986, 126, fig 52, nos. 164 & 166; Crummy 2005, nos. 16 & 18; Jackson and Burleigh 2018, 288, fig. 336, cat. 6.33, 6.34 & 289, fig. 337, cat. 6.33, 6.34, 1st-century AD). “

The permission where I found this segment of bracelet is not too far from Baldock and Ashwell, so it fits with the suggested concentrations found in Hertfordshire. I unearthed this find a few hundred meters from the suspected Roman farmstead. Could this bracelet have belonged to a retired Roman soldier living out the remainder of his days at the side of the Roman road that ran past this enclosure? I guess we will never know, but it’s wonderful to imagine the people that these sometimes once prized possessions belonged too.

A Southern Gaulish rarity

The most significant find to come from this permission is a coin that inspired the first coins minted in Britain, and it made its way to these shores from Southern Gaul (Figs.20a & b). This coin has now been registered on the Portable Antiquities Scheme, so I think it’s best to leave this with the description provided by Matt Fittock my Finds Liaison Officer.

“A Southern Gaulish copper-alloy (bronze) unit struck on a cast flan from the Gallic city-state of Massalia (Marseilles), probably dating to the late-3rd or early-2nd centuries BC, c.250-150 BC. Obverse: Laureate head of Apollo left, surrounded by beaded line. Reverse: A bull butting right, standing on exergual line, the legend MA above. ABC p. 32, no. 115.”

“This appears to be a Gaulish import of Massaliot type rather than the later British ‘Thurrock’ or Kentish cast potins that derive from the Gaulish types (e.g. ABC no. 120). Similar examples have been recorded in Britain and through the PAS (e.g. BH-96C0C1, ESS-5BFC67, BERK-838D00) and likely date to the later-3rd or early-2nd centuries BC, probably from the earliest phases of copies of Massalia’s bronze coinage in Gaul or genuine late issues of Massalia herself. This is a find of note and has been designated: For inclusion in British Numismatic Journal ‘Coin Register’.”

It turns out that this is an incredibly rare find in the UK with only 10 finds appearing on the PAS database (at the time of writing this article) when you search with the term “bronze Massalia unit”. It does make me wonder what a trader from Southern Gaul was doing in this field in North Hertfordshire well over 2000 years ago. The fact that I found this coin just outside the suspected Iron Age enclosure might suggest that some significant trades were taking place here? Or maybe the trader was just passing through and dropped the coin, we could guess at the possibilities of this story forever.

This is only the second time that I have had one of my finds listed as “A find of note” on the Portable Antiquities Scheme, the first being a rare late Iron Age loop and toggle fastener. I donated the toggle fastener to my local museum and I intend to do the same with this coin when I get it back. I think finds like these are better left for public view in a museum rather than collecting dust hidden away on a shelf in my house.

Slim pickings

I have been detecting around this permission, on and off, for just over a year now and the finds pouch seems to be less full every time I go. The last few outings have been very fruitless which feels disheartening given the quality and rarity of some of the finds that have come up during that time. I feel sure there will be more to find here but it might take the magic of the plough to bring these things close enough to the surface for me to find. In a strange twist, on my last visit I found next to nothing until the last half hour when I decided to detect on the side of the river where I had previously found very little. In that half hour 5 coins came up, admittedly they were all pretty toasted apart from a silver Victoria threepence which was in ok condition, so maybe it’s time to do more walking on that half of the permission, hmmm?!

Detecting, writing & work

It’s that time again where I’ve had another of my articles published in Treasure Hunting Magazine, and this time it’s more of an interview based affair with the retired archaeologist Gilbert Burleigh. It all came about through a chance meeting on a Facebook group, which led to me meeting Gil and talking about his long career, his valued and trusted relationships with detectorists, and the wonderful archaeological discoveries that those relationships have unearthed. This particular article was published in the May 2024 edition of Treasure Hunting Magazine but is also available to read here on the Hertfordshire History Hunter blog.

It’s always a great feeling to see my articles published in the magazine, but things have gone that one step further as I’m back working on the magazine again. Around this time last year the guys at Treasure Hunting approached me to help out with the layout of a few sections of magazine whilst their design and layout department were busy with other projects. I did this for a couple of issues working on News & Views, Readers Finds and Auction Round-Up. Things worked out pretty well and it was fun to get my hands dirty doing magazine work again, a design discipline I hadn’t been involved with since the late 1990’s.

So, just recently I have been asked to help out on the magazine again but this time round it wasn’t just a couple of sections, it was the whole magazine. The guys at Treasure Hunting were in the process of looking for a new artworker, so they asked if I would cover for a few issues to give them time to find the right person for the job. I was more than happy to help out as I really enjoyed working on the magazine last time around, and again it’s proved to be an enjoyable experience.

Obviously there was a lot more work to do this time, but on the whole it fitted in quite well around the existing design work that I had in my schedule. So for the May and June editions of Treasure Hunting Magazine in 2024 you will see my name under the layout & design credits on the contents page. But in a strange twist of fate the only article that I did not layout for the May edition was my own. This had already been put together for a previous issue which the editor pushed back to the May edition. Still, I can’t complain because I see it as a privilege to work on the magazine, and as Julian Evan-Hart said to me in one of our email conversations, “who’d have believed our first contact would have led to this eh?”. But led to this it has and it’s been brilliant working on the magazine again and I’m sure it won’t be the last time.

It has to be said that this hobby has enriched my life way beyond my expectations, and I can’t thank my partner Heather enough for buying me the Equinox 600 for my birthday in 2020. The 600 has now been upgraded to the 900, but I have kept the 600 as backup (it’s too good a detector not to keep it). This hobby really has filtered through into all aspects of my life which now includes work, and I wonder, can this hobby give anymore? Well actually yes, if the detecting gods are listening, that hoard of gold Romans coins would be nice to discover in the not to distant future. Lol, joking aside, this hobby has already bestowed me with more than enough riches for which I will be forever thankful (but that hoard would be nice).

Gil Burleigh – archaeologist

Somebody, somewhere said to me that a great way to obtain permissions is to politely ask the question on Facebook community pages. Specifically ones which are hosted by villages, the reasoning being that local farmers and landowners are more likely to be living in villages than big towns and cities. I liked the logic so I decided to give it a go. I put out a small post on several community groups of the local villages near me and waited for the permissions to roll in… hhmmm!

I would love to say that the permissions came in by the bucket load… sadly they didn’t, but I did get a response which led me to writing this article. I had some inquisitive and very positive comments which was really good to see, but one comment mentioned that there was a battle site close to one particular village which involved King Offa (Fig. 1). This is something I had read about in local history books so I thought it was fact, but then another member of the village replied with the following insightful post.

“This is a local myth that arose in the 19th century after quarrying in the 1790s and 1830s uncovered the remains of a graveyard in which some of the skeletons were accompanied by weapons – swords, spears and shields. Nineteenth century antiquarians leapt to the conclusion that the burials must have been warriors killed in a battle between Anglo-Saxons and Danes – hence the subsequent name given of Dane Field (Fig. 2). More likely it is an earlier pagan Anglo-Saxon cemetery when it was not uncommon for some of the dead to be buried with their weapons, having usually died of natural causes, not in battle. Archaeological excavations on the field close to the burial ground in the 1990s revealed an early Anglo-Saxon settlement to which the cemetery probably belonged. I’m an archaeologist and resident of the village and have been working with responsible metal detectorists for nearly fifty years, if you want to get in touch.”

It goes without saying that I got in touch, and to my surprise the archaeologist in question was Gilbert Burleigh. Gil has been involved with some major archaeological discoveries in his time, some of which will be discussed and displayed within this article. But the thing that struck me, as I’m sure it has you, is the fact that Gil has been working with responsible detectorists for nearly 50 years. I was quite taken aback by his statement, an archaeologist working with detectorists since the very beginnings of the hobby in the 1970’s? I was lead to believe that during those early years archaeologists absolutely detested detectorists? There is an old saying that ‘never the twain shall meet’, and as you will see it resulted in the discovery of some amazing treasures. As a side note I think there’s inspiration here for Mackenzie Crook to write a new series, maybe Andy and Lance as kids trying out their first detectors and the 1970’s/80’s soundtrack would be brilliant. Apologies, I daydream and digress.

After making contact and a few email communications later, Gil agreed to let me meet with him to discuss his career, the archaeological delights that he’s been involved with and more surprisingly his inclusion of metal the detecting community. Before we met, Gil was kind enough to provide me with a short autobiographical background about his career, with in which was the following insight to his views and relationships with detectorists (it’s almost like this article is writing itself).

“Over the years, some people have said to me that I’ve been very lucky in some of the spectacular discoveries I’ve been involved with and I reply that one can help make one’s own luck. For example, at North Herts Museums I began recording responsible metal detectorists finds in January 1976, in the early days of the hobby. Like the late Tony Gregory at Norfolk Museums and Kevin Leahy in Scunthorpe, independently, I continued recording their finds and working with them all through the years, including the many years from the late 1970s through to the late 1990s when the detecting and archaeology communities were, largely, vigorously opposed to each other.”

“I took the pragmatic view that the detectorists would carry on detecting regardless of what archaeologists thought, so we might as well record as many finds as possible. Most of the archaeological community finally came to this view with the launch of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) in 1997. I think that because I had good relationships with many in the local detecting community they brought their finds to me for recording between the beginning of 1976 and the end of 2003, when a PAS officer, Julian Watters, was appointed for Herts and Beds, based at the Verulamium Museum in St Albans (Fig. 3).”

Photo copyright St Albans Museums.

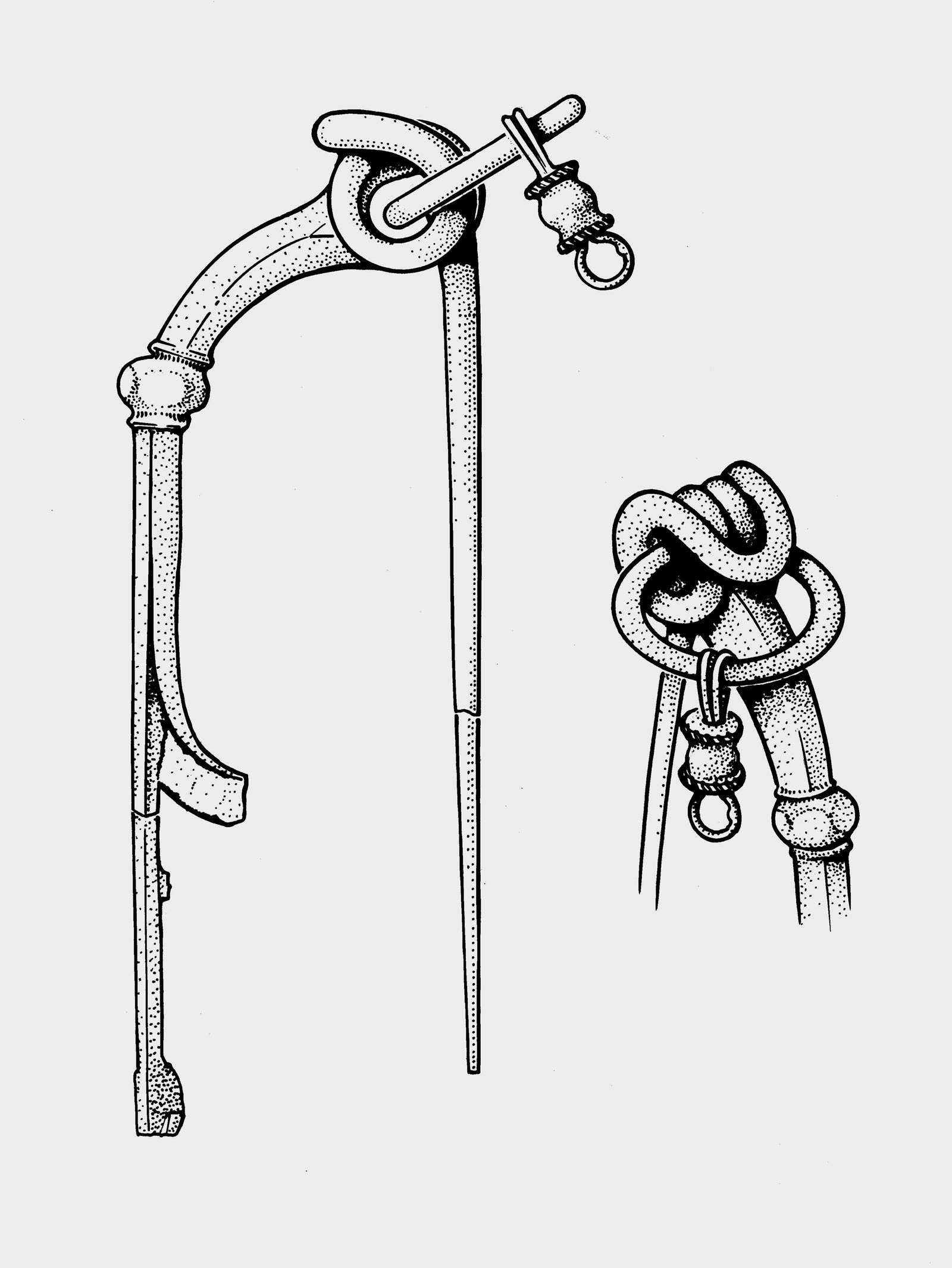

“For several years after his appointment, I assisted Julian with the recording of finds from North Hertfordshire. In return the detectorists received expert written identifications, accompanied by top-quality illustrations (Fig. 15) of their finds. Undoubtedly, because of this carefully nurtured relationship over many years some extraordinary finds were reported to me by detectorists which might not have been had the good relationship not existed.”

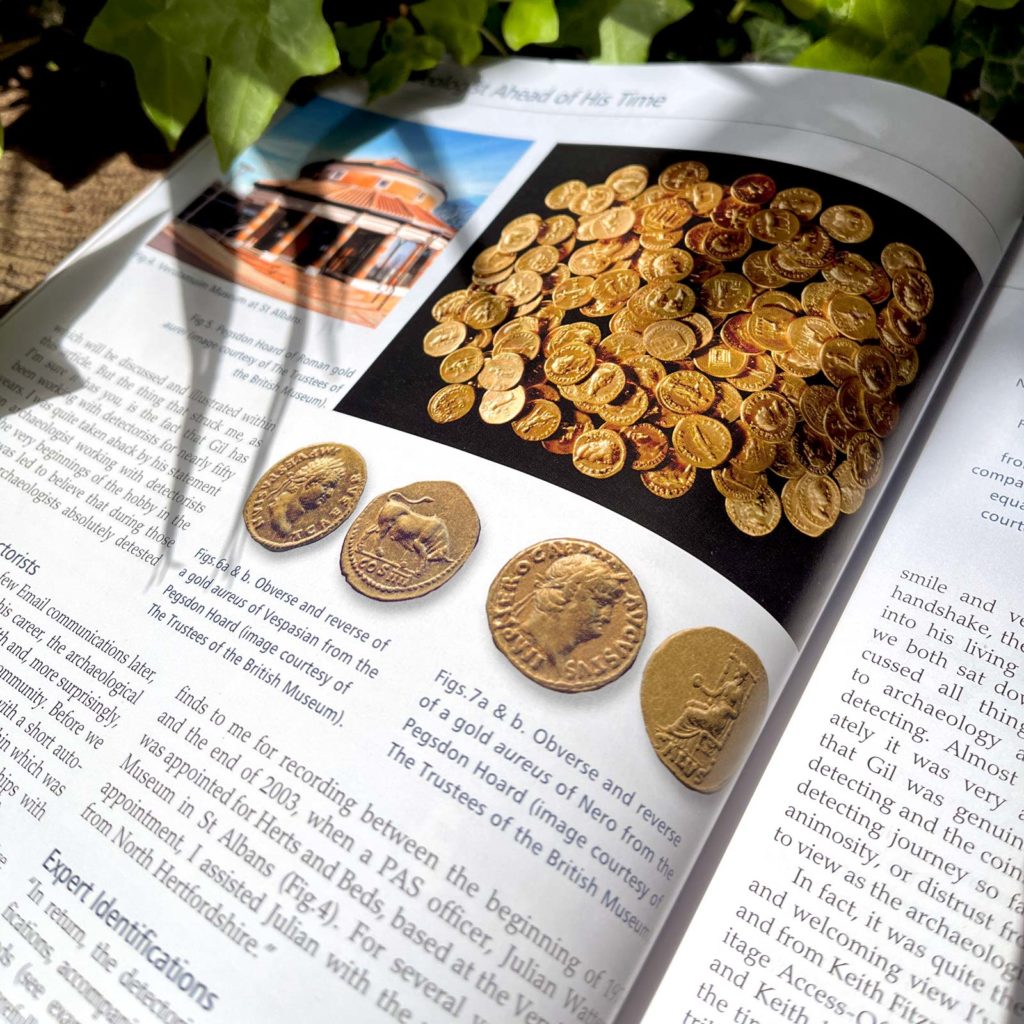

“Amongst these, I count the unique Pegsdon 1st-century AD Roman gold coin hoard found in 1998 (Curteis and Burleigh 2002); the Pegsdon 1st-century BC Iron Age decorated copper-alloy mirror and accompanying silver bow-brooch found in 2000, from a cremation burial, one of the earliest and most complete in the contemporary mirror series (Burleigh and Megaw 2007); and the Ashwell 4th-century AD Roman gold and silver temple treasure hoard found in 2002, only the third such hoard found in Britain and the first since the 18th-century (Jackson and Burleigh 2018).”

Meeting gil

It was a weekday afternoon when I met Gil who had very kindly invited me to his home. He greeted me with a warm smile and very welcoming handshake, then showed me into his living room where we both sat down and discussed all things relating to archaeology and metal detecting. Almost immediately it was very apparent that Gil was genuinely interested in me, why I got into detecting and the coins and artefacts that I had found on my detecting journey so far. There was no sense of snobbery, animosity or distrust from him which a lot of people seem to view as the archaeologists standard stance on detectorists. In fact it was quite the opposite and it’s the same warm and welcoming view I’ve had from My Finds Liason Officer Matt Fittock and from Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews the Curator and Heritage Access-Officer at North Herts Museums. Both Matt and Keith have been very patient and accommodating in the time that I have known them and they have also contributed to some of my past articles which have featured in Treasure Hunting Magazine.

Chatting with Gil went at a very leisurely pace and it was great to get more insight from him about the wonderful discoveries he has been involved with which he puts down to his long lasting relationships with detectorists. Gil has also very kindly provided a lot of the imagery for this article from the sites’ archives, so there is plenty for all of us to ogle at. But the best thing is that all of these wonderful treasures were found by detectorists, which gives me hope that one day you or I could be the finders of such amazing artefacts. Before we met, Gil provided me with his CV to read which included more detailed information about each of these discoveries, so I have included some extracts from those as well as Gil’s personal insights he discussed with me. Hmmm, this article is back to writing itself again.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Pegsdon gold coin hoard

“Shillington A & B, Bedfordshire: 127 aurei to AD 78, 18 denarii to AD 128”, in Richard Abdy, Ian Leins & Jonathan Williams (eds.), Coin Hoards from Roman Britain Volume XI, with Mark Curteis, 2002, Royal Numismatic Society Report on the discovery by metal detectorists in 1998 of an early Roman hoard of gold coins and its significance.

The Pegsdon Gold coin hoard (Figs. 4, 5 & 6) is a discovery that I personally remember as it was often talked about down the pub at the time. This was way before I got into detecting but it was one of those things that became a bit of local legend as there was speculation about the amount of money that the detectorists received for finding the hoard. When I asked Gil about his memory of it I stayed away from the monetary side of things and he recounted the following.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

“The hoard was found in 1998 and that is an interesting story. The two detectorists who found the hoard, who were on the land with the permission of the land owner, discovered it just a stones throw from the main farm house. They had been reporting things to me off and on for a few years up until that point, but this particular day was a day off of mine and they called me on my home phone and said, “Gil, we have something that you might like to see”.

“A couple of hours later the two detectorists turned up at the house with a brief case and proceeded to tip the contents of it onto the kitchen table. There was something like 112-113 gold Roman coins in mint condition that were staring back at me. The detectorists told me they had all been found in a relatively compact area, so I said we have to go back because there’s going to be more!”

“So myself and the two detectorists went back to the site and we started searching outwards from the find spot. We found another 16 gold Roman coins, so that made it 127 gold aureii in total. We found these along with some other silver denarii, I suspect they were from a separate hoard which were later in date, second century I believe and there were around 17 or 18 of those.”

Photo by Jane Read, North Herts Museums.

crested owl plate-brooch. The owl was a companion of Minerva who was equated

with Senuna. Enq.2308. Photo by Jane Read, North Herts Museums.

Photo by Jane Read, North Herts Museums.

Hearing Gil recount his memory of the gold Roman coins made me think how amazing it would be to find even one such coin, but 127 that are in mint condition, that really is the stuff that dreams are made of! Gil also provided some images of other finds that have been made around the same area (Figs. 7, 8, 9 & 10) which are also amazing artefacts in their own right.

Pegsdon Iron Age mirror

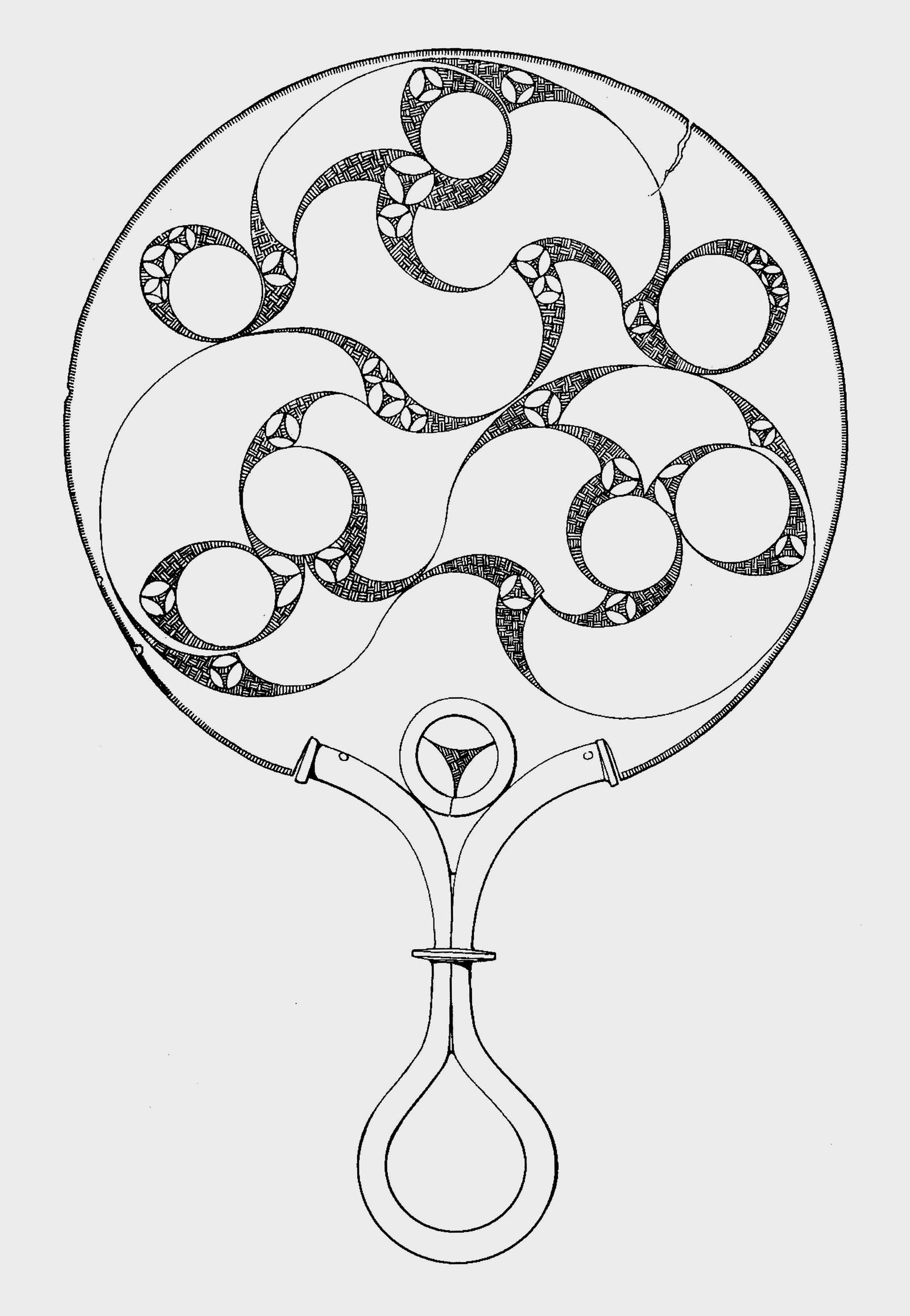

“The Iron Age mirror burial at Pegsdon, Shillington, Bedfordshire: an interim account” With Vincent Megaw in the Antiquaries Journal, vol. 87, 2007, pp.109–40; Society of Antiquaries of London

Abstract: In November 2000 metal detectorists located a decorated copper-alloy mirror, a single silver Knotenfibel brooch and some pottery sherds at Pegsdon, Shillington, Bedfordshire. Subsequent excavation of the findspot uncovered a Late Iron Age cremation burial pit associated with further pot sherds and a single fragment of calcined bone. The opportunity is taken in this preliminary account to revisit both the occurrence in southern England of the brooch type and to discuss the mirror’s decoration in relation to the variation of views as to the British mirror series as a whole, and in particular with regard to other recent mirror discoveries. The burial is discussed in its local context and the possible significance of the topography in relation to the site is highlighted.

It amazes me that the things we unearth are sometimes in superb condition, especially with the amount of time they have spent in the ground. In the case of the Pegsdon Iron Age Mirror (Figs. 11 & 12) that’s over two thousand years. But it also amazes me that these things often shed light on the fact that day to day life 2000 years ago was not all that different to how it is today. Even back then taking pride in your appearance was made all the easier with the use of a mirror, although I do believe they had a lot more significance and meaning than they do today. Gil reflected (see what I did there, lol) the following about this wonderful find…

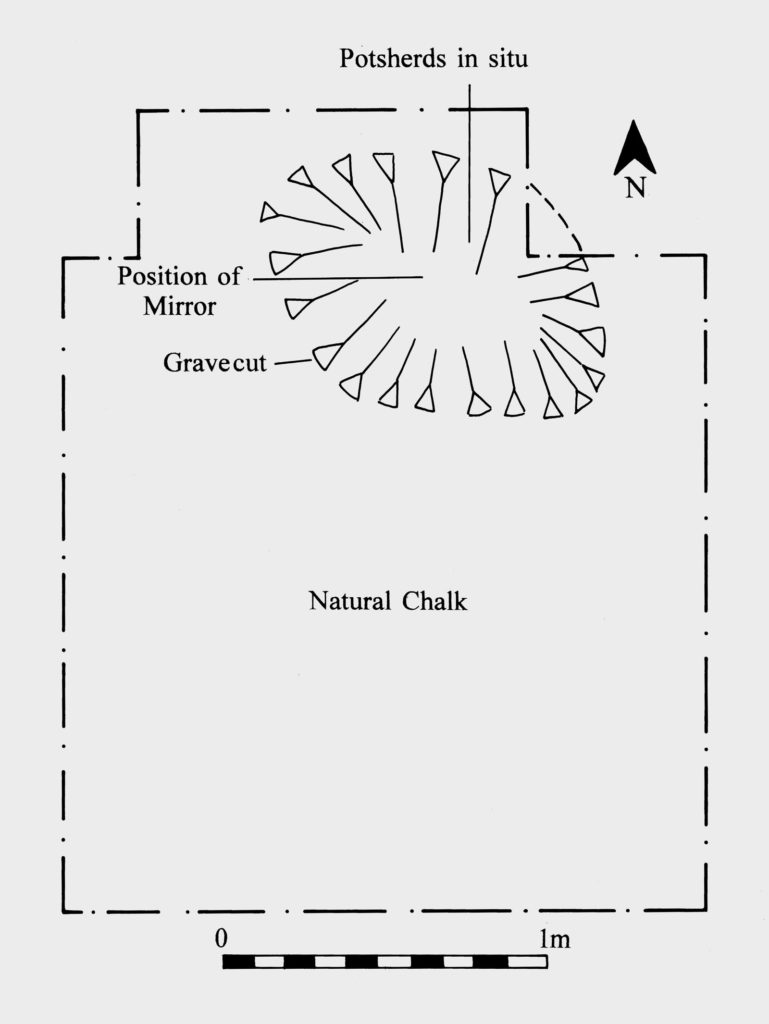

“A few years later the same detectorists who had found the Roman gold coin hoard found a late Iron Age decorated bronze mirror accompanied with some broken pot fragments along with a silver brooch which was also late Iron Age (Fig. 13). This time we couldn’t go back to do further investigation at the find spot until a year later because of crops being sown and the farmer didn’t want us poking about (incidentally this was the same field that the Roman gold coins were found in). So when we did go back to carry out a small excavation, just the two detectorists and me, I was able to define a grave pit”.

“There had been a cremation burial in a pot with a pedestal base, a very distinctive late Iron Age urn type, accompanied by a flat-based jar, and we found some more fragments of the urn along with some cremated bone. With that I was able to work out where everything was positioned in the grave pit (Fig. 14), it’s incredibly useful to be able to put the discovery in its archaeological context, which as an archaeologist is the main thing you want to achieve, so that was brilliant”.

“Of course, Iron Age mirrors, rarely found artefacts, were of much greater significance than simply for personal grooming, with their implied attributes of power and of the magic associated with the imagery of light and reflection, fire-making, and capability to dazzle, they were used in religious ceremonies to impress, usually by priestesses; for when associated with burials the identified human remains are almost all female”.

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

“The mirror itself was intact but with the detectorists eagerness to get it out of the ground they were a little bit rough with it, so it had split in a couple of places. When it was conserved that was all repaired but surprisingly the handle was still attached, usually you find these things are separated buy the plough so it’s quite rare to find something like this in one piece. So it was in pretty good nik really, and the decoration had been very well preserved, it would have been polished on one side with the decoration on the back”.

“The silver brooch (Fig. 15) found with it would have been part of a pair that were connected by a chain, but as is often the case you get one of the pair and you don’t ever find the other one. But I think in this case where we found a brooch which was quite quite obviously of a pair, the reason we don’t find the other one is because it wasn’t put in the ground in the first place. It may have been deliberately separated so that the mourners kept it as keep sake as way of a connection to the burial. The detectorists did search far and wide for the brooch’s twin and the chain but they never found anything, which is why I came to the conclusion that it was never in the ground in the first place”.

“As an archaeologist you know that these things are being brought to your attention because over the years you’ve built up a relationship with the hobbyists out there detecting, and then they trust you, and you in turn trust them, sometimes ending up with spectacular results. It’s all about relationships and trust”.

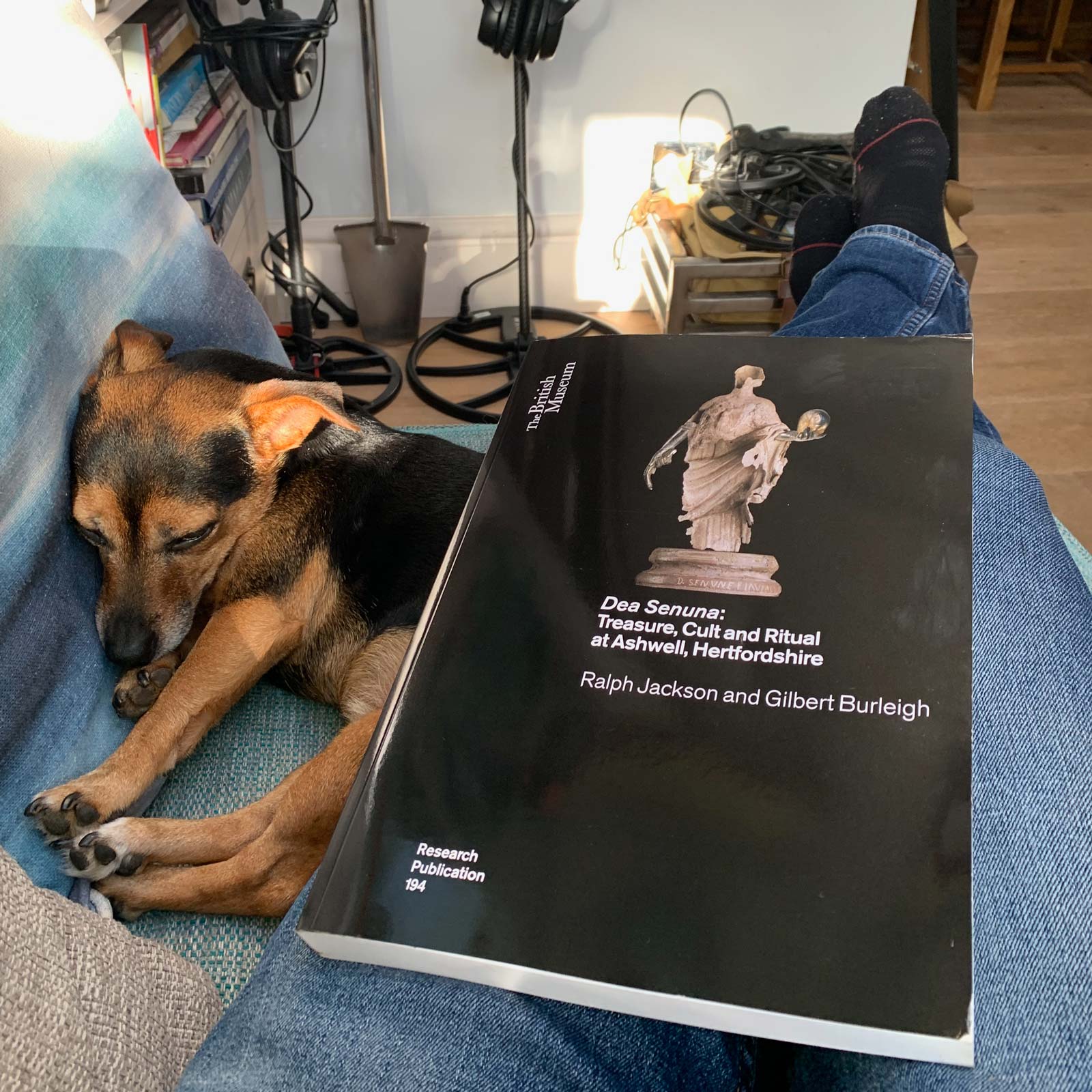

Sea Senuna the unknown deity

Dea Senuna: Treasure, Cult and Ritual at Ashwell, Hertfordshire, with Ralph Jackson and other contributors, March 19, 2018, The British Museum

Abstract: The Ashwell Hoard is an unprecedented find both in Britain and in the wider Roman world. In Britain there has been no equivalent discovery of ‘temple treasure’ within living memory. It is paralleled only by the 18th-century finds from Barkway, Hertfordshire (1743) and Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire (1789). In contrast to the Ashwell Hoard those two finds preserve almost no information concerning their discovery or archaeological context. In terms of its finding circumstances, then, the Ashwell Hoard is exceptional even amongst the small number of precious metal votive hoards from Roman Britain. But it is exceptional in other ways, too, most notably in the inclusion of a silver figurine, unique gold jewellery and votive plaques of gold and by the proportionately large number of plaques with votive inscriptions and with die-stamped figural decoration. The silver figurine of Senuna, a hitherto unknown native British goddess, is unparalleled in Roman Britain. If the dedication of a large, high-quality, silver-gilt figurine is evidence of a votary of some means amongst the followers of Senuna so, too, and even more so, is the gold jewellery, which may be interpreted as a suite. It is a very rare survival outside Rome itself. Numerically, the greater part of the Ashwell Hoard is the collection of 20 gold and silver votive leaf plaques, which, in form and number, are a unique survival. The importance of the hoard, whose ‘new’ goddess caught the imagination of the public as well as the academic world, was such that it demanded an archaeological investigation of the find-spot. Its discovery triggered the fieldwork that illuminated the immediate setting of the hoard and then expanded that setting into the wider landscape. The progressive results of fieldwalking, geophysical surveys and excavations led to a fuller understanding of the circumstances surrounding the choice of site for the burial of the hoard, of the nature and use of the site itself and of its relationship to surrounding structures, settlements and natural landscape features. Almost the first find from the excavations was the missing silver pedestal from the silver-gilt figurine, a key find, and, better still, inscribed. In reconnecting the image of the female deity to the dedicatory vow, inscribed for the votary Flavia Cunoris, it instantly multiplied the meanings and hugely enhanced the significance of an already important object. That discovery set the tone for the excavations, which went on to reveal not a formal temple building, as initially suspected, but a unique and fascinating open-air ritual site, where feasting, religious activity and ritual deposition took place over a long period of time, seemingly extending as far back as the Bronze Age.

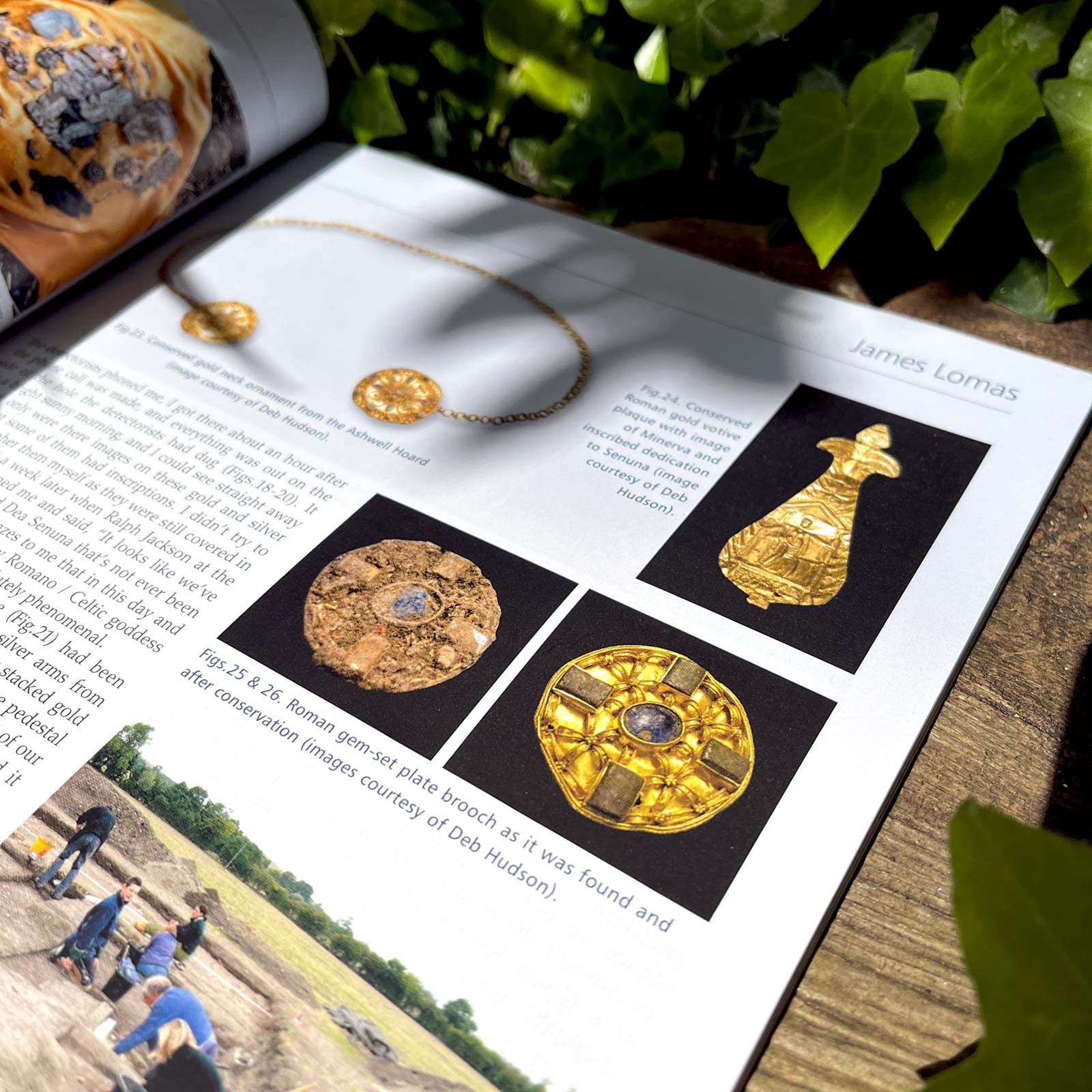

So the Ashwell Hoard (Fig. 16) is the big one in the context of archaeological significance, it was the discovery of a deity that had never been heard of or recorded before. I could see by the beam on Gils face and the enthusiasm in which he spoke about this discovery that it was the biggest highlight of his long career. And again it’s something that Gil freely admits would not have been possible if it weren’t for the detecorists who were out searching the fields that day. The good relationships that Gil had built with local detectorists over the years certainly paid dividends for the archaeological world with this incredibly significant find. With a glint in his eye Gil recounted the following about this wonderful treasure.

“I went out to the site on the day the detectorists phoned me, I got there about an hour after the phone call was made, and everything was out on the side of the hole the detectorists had dug (Figs. 17, 18 & 19). It was a bright sunny morning and I could see straight away that not only were there images on these gold and silver plaques but some of them had inscriptions. I didn’t try to read and decipher them myself as they were still covered in dirt. It was about a week later when Ralph Jackson at the British Museum phoned me, he said, “It looks like we’ve got a new goddess called Dea Senuna that’s not ever been recorded before”. It still amazes me that in this day and age you can come across a new Romano/Celtic goddess that’s unrecorded, and that’s absolutely phenomenal.”

“If I remember rightly the figurine (Fig. 20) had been placed on top of the gold jewellery and silver arms from the figurine, beneath which were the closely stacked gold plaques and then the silver-alloy plaques, but the pedestal base for the figurine was not in that pit. At the start of our excavations it was found about 5 metres away and it appears to have been deliberately buried separately. You can never really understand why people do these things, but they did, and that’s how we found it. It was definitely the base for the figurine which the conservators were able to prove without doubt because the figurines feet matched with the outline of the solder on the base. Why they would bury these things separately is anyone’s guess, but it may have been that one person had buried the bulk of the hoard and a relative was burying just the pedestal base as their separate and personal act of ritual.”

Gil carried on to say…

“Again on the Ashwell dig, and this was also deliberate I’m sure, we found part of a copper alloy plaque depicting a bull placed on a surface on one part of the site right in the centre of the ritual enclosure. We found the other half of the plaque deliberately placed in a little pit a few meters away. They were very clearly broken, separated and then buried separately for whatever motive, who knows. It could be two different devotees making an offering of one thing but they each wanted to make a separate offering so they broke it in two.”

and inscribed dedication to Senuna. Photo by Deb Hudson.

It was great to hear Gil’s recollections of these amazing discoveries and even better to be able to share them, along with some of the photos from the sites’ archives as well as other photos which Gil has provided (with permission) for use in this article (Including Figs. 21-25). Gil was also involved with more extensive excavations that took place at Ashwell in the following years which produced further insight to add to the archaeological understanding of the area (Figs. 26 – 33).